Brand Hijacking

Photo: Getty Images by peshkov

Requests for artwork and designs using other brands' intellectual property without permission—honest mistake or not—are a growing challenge for distributors. What's the motivation behind the practice, known as brand hijacking, and how can industry companies address it?

Share Article

by Joseph Myers

August 2019

Let’s open with a hypothetical scenario. A nonprofit client comes to you with a request. The Super Bowl is right around the corner, and the organization is hosting a fundraiser viewing party for supporters with a pop-up shop on site to raise a little extra cash. The nonprofit needs a couple hundred T-shirts, a few dozen water bottles, maybe some stickers, all decorated with a special “Super Bowl Watch Party” design incorporating its logo and a silhouette of the Lombardi Trophy. You’re eager to help, of course, but you know that using the words “Super Bowl” is a no-go, as the NFL owns the trademark. You suggest that the organization go with “Big Game Watch Party” instead. The rest of the design remains the same. Your client places the order.

It was almost a good catch, but there’s a problem. The NFL owns the rights to the Lombardi Trophy design, too—even the silhouette. Depending on how litigious the league is feeling, that pop-up shop merch could bring legal action against your client. That may only mean a cease and desist. But it could mean more. Either way, getting caught with your hand in the IP cookie jar is a bad look for everyone.

If you’re even a casual follower of trademark infringement cases, you’d probably have caught the trophy mistake. The NFL is notoriously protective of its intellectual property, after all, and these kinds of cases make headlines all the time, usually as the Super Bowl nears. Here, it was an honest mistake. Your client was just trying to have some fun and raise some money for a good cause, not deliberately rip off another brand. But, sometimes, the requests are not so innocent—they’re attempts to quietly cash in on someone else’s hard-earned IP.

The practice is known as brand hijacking (not to be confused with the similar practice of using competitors’ names or trademarks in paid search keywords). And far too often, cases of it—intentional or not—are much murkier and harder to spot than the Super Bowl example above, especially when the IP in question isn’t as well known as the NFL’s.

To explore what it all means for distributors (and suppliers), the psychology behind its increasing presence in the field, and what can be done to combat it, Promo Marketing connected with Craig Davidiuk, owner and marketing director, Ultimate Promotions, 100 Mile House, British Columbia; Joshua White, general counsel and senior vice president of strategic partnerships for BAMKO, Los Angeles; and Rob Ross, president of Chamberlain Marketing Powered by HALO, Taylor, Mich.

Through these conversations, it became clear that though we live at a time where industry businesses can fulfill clients’ orders faster than ever, that quick pace can end up being a double-edged sword, owing to the temptation to make a quick buck, even if it means skirting the rules and jeopardizing reputations. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

Elephant in the room

Even in the time it took you to read this article’s introduction, the world’s population grew significantly, and that immense total will swell even more as your eyes scan the rest of the contents. Since mathematics reminds us that we have never seen more people gracing the face of the earth than we are doing now, we could feel that the vast numbers make us seem disconnected because we are all doing “our thing.”

A little something called the internet has played the role of unifier in the commercial sense. Thanks to its global emergence, the world has become smaller, according to Ross, with that figurative shrinking coming as a source of hope for business-minded folks, but also one of worry for those who always want integrity to be the hallmark of economic transactions. The initial part of that equation means that brands are expanding their scope internationally, but no matter whether companies are dealing with domestic requests or gaining clout overseas, the perennial pest, brand hijacking, is there to be its irksome self.

“When I was in private practice, it never even occurred to me that brand hijacking was something that took place,” White said. “However, I saw a lot of other instances of companies taking deceptive actions to try to mislead consumers into placing a higher value on their product. That’s really what brand hijacking is—trying to exploit the value of someone else’s brand to create an artificially inflated value on your own brand or product.”

In many respects, brand hijacking—the deliberate kind—also resembles the I-wish-I-could-have-created-that mentality that we hear among writers and creative individuals who are looking to commend their contemporaries. With these situations, though, hijackers, rather than attempting to contribute something unique for consumers’ consumption, simply yield to an I-can’t-outdo-them-so-I’ll-steal-from-them yearning and compromise the legitimacy of those on the straight and narrow.

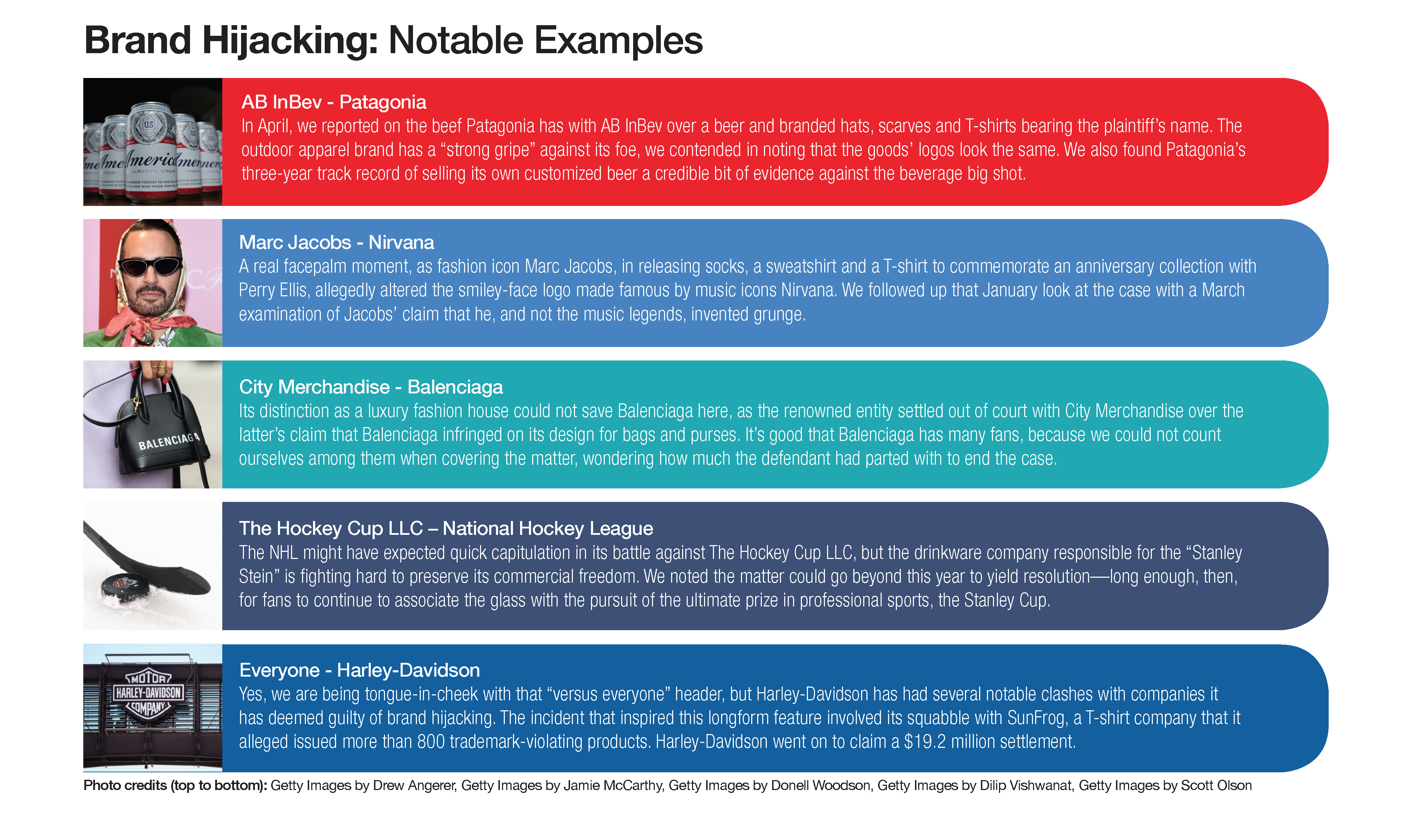

On our website, we’ve covered numerous high-profile instances where businesses have gone after equally renowned institutions and smaller establishments for alleged copyright violations and trademark abuses. Nirvana and its confrontation with Marc Jacobs over T-shirts. Harley-Davidson and its gripes with, well, lots of brands, including SunFrog, Affliction and Forever 21. The NHL and its legal tussle with a drinkware company over Stanley Cup mugs.

These and many more examples (see graphic below) all inspire causes for concern among promotional products industry constituents. With so many people involved in the manufacturing, supplying and distributing of goods, one bad apple does not have the power to spoil the bunch.

But what about the effect that many such tarnished presences can have on everyone? We would have a difficult time in thinking of a field that does not, in any way, occasionally find itself defending its standing due to judgment errors by practitioners.

The promotional products industry specializes in being an efficient, trustworthy and professional partner—a solutions-provider for clients. Putting them at risk of legal trouble due to lack of preparedness—or, worse, intentionally engaging in questionable practices—can harm that reputation.

“I feel that brand hijacking is more prevalent now than ever,” Davidiuk said. “There’s no pretty way to put it. I see it as a huge problem because there are some people out there who just fail to place any respect in brands and the hard work behind them.”

There is also no attractive way to state that brand hijacking can be an elephant in the room for industry figures to discuss. In fact, Promo Marketing met with rejection from a few sources that found the matter either too controversial or too layered to address. Davidiuk, however, proved the most vocal, having approached us with the idea of covering the topic as a means to raise awareness for distributors.

Having made his pitch after reading one of our accounts on Harley-Davidson, Davidiuk revealed that clients occasionally come to him and his hires with requests to place such items as major brands’ artwork, “bastardized versions” of it and celebrities’ faces on goods.

All of these, if put to product, could count as instances of brand hijacking. Davidiuk said he turns these requests away. But for distributors with less knowledge of the legal restrictions and ramifications—or those who know the rules but just want to make a quick buck by looking the other way—these kinds of sales could be trouble.

Brands that use another entity’s intellectual property on promotional merchandise without permission are setting themselves up for legal trouble if the IP owners take notice. If that happens, it’s a problem for both the client who asked for the design and the distributor who delivered it.

“Staying focused at every turn has to be what guides your identity as a business figure,” said Davidiuk. “But, and this is going to sound surprising, I personally think that if I contacted 10 companies to produce off-brand Mickey Mouse pins, T-shirts or cups, nine of them would take the order. The urban myth that ‘If I change Mickey so that he has neon ears and no face, it’s my own art’ is alive and well. Unfortunately, it’s 100 percent wrong. I think we all have Andy Warhol to blame for that. He’s the most famous brand hijacker of them all.”

A growing concern?

While one could argue that the pop art pioneer gained significant regard for derivative work, that same person could say that anyone who tries that approach now, on a grand or minor scale, could be infamous for far more than 15 minutes. Like Davidiuk, Ross holds that brand hijacking poses a risk to the value that they and their peers look to bring to every project, and that it will likely remain a pest for a considerable period.

“We have the task of being brand police for clients,” Ross said of a duty that he and other promotional products professionals should treat with the utmost respect. “We have information-gathering and competitor-tracking as tools to assist in that regard. And though those are great, so, too, is the motivation that brand hijackers have to go against the grain, making policing increasingly cumbersome.”

Ross noted he supposes that brand hijacking most frequently occurs in the form of “one-off items for individual consumption.” That desire for quick fixes finds an ally in what he sees as a new generation of printers that is quite willing to overlook the securing of permission to use a protected piece of IP.

“It shouldn’t sound too surprising that most people who engage in [brand hijacking] feel they’re not doing anything wrong,” he said. “Their moral compass, so to speak, becomes stuck because they’re in it only for themselves. But there are so many complications for consumers, who could end up hurt, depending on the quality of the knockoffs, and the companies, who will have had their operations questioned—because people who run into trouble with bogus products are going to go after the trademark holder, or what have you, and not the people who had put them in the bind.”

“Proper usage,” therefore, resounds as a huge consideration for all parties, with everyone knowing that those who wish to go against reason to make a buck could not care less about the repercussions of their actions. No matter one’s business-related lot in life, the threat of brand hijacking is a real one, for even if a company has become well versed in warding off unlawful requests, any instance of a corruption of someone’s brand resonates among that enterprise’s whole identity.

It might not sour it, if we were to refer back to the “bad apple theory,” but it can, and does, inspire sympathy among industry heavyweights for their troubles. Even the possibility of it also leads legitimate industry movers and shakers to sharpen their diligence. For Davidiuk, who has come to prominence through selling enamel pins, that has been an educational experience.

“Every day, when I log onto Instagram, I see at least five new suggested accounts for new people who are planning to create and sell enamel pins online,” he said. “I’d say about 30 percent of those people are creating art that involves Marvel characters, ‘The Simpsons,’ celebrities and brand remixes, such as changing the words ‘Campbell’s Soup’ to another message but maintaining the look and feel of the brand.

“We really struggle with video game characters like Pokemon or Warcraft,” he continued. “I’m not a gamer. My staff is over 35 and doesn’t game. How are we supposed to know that we’re not creating art out of video game characters? In one case, our designer’s teenager picked up that his mom was working on a pin that was a Pokemon character. We had to turn the order down. There is only so much pop culture one 47-year-old man can absorb, and this issue does worry me as a business owner.”

One might argue that distributors and decorators signed up for this when they entered the industry, and, yes, that is true to an extent. But the strain can grow intense. Davidiuk noted that companies have become especially protective of their holdings, and that people have grown increasingly cunning with trying to see their commercial aspirations come to fruition.

As an example of the latter, he talked about Etsy as a location where there are “thousands of items that violate copyright law,” suggesting a search for “David Bowie” as an example. He also wondered just what businesses are to do when a customer can buy goods directly from China or through “five other distributors” with no questions asked.

Regarding the former point about better protection of intellectual property assets, Davidiuk, who also singled out Shopify, Squarespace and similar “easy-entry” e-commerce platforms as brand hijacking accomplices, explained the provocation behind brand hijacking, both among clients and those they approach, and relayed a personal example to detail the watchdog nature that companies should exact if they care deeply about their identity.

“I feel at the end of the day, morals will take a backseat to a $2,000 sale,” said Davidiuk. “People think they won’t get caught. What distributors do not realize is [that] big brands hire legal firms to go after violators. Google the term ‘brand endorsement,’ and there are thousands of results, so that industry is alive and well. [Companies] use employees posing as real people on social media, and they search for and prosecute violators, much like the insurance industry does to catch fraudsters.

“Fifteen years ago, I was the vice president of a mountain bike club in British Columbia in a town of 10,000 people,” he added. “One day, we got a cease and desist letter from Harley-Davidson regarding our logo. Note that Harley is located in Milwaukee, which is 2,000 miles away. Facebook wasn’t really around yet. We had 200 members and our website got maybe 400 visits a month. Our logo was a hand-sketched, line art drawing of mountain bike handlebars and a race plate. It didn’t look that close to their brand, but it was close enough to catch the eye of Harley’s legal team. Our choice of font, which was hand-drawn, was too close to their typeface. Our logo was black and white. Harley’s is color-filled. We had to change the logo at the end of the day.

“[Harley-Davidson] has been very aggressive about pursuing brand hijackers, and sued Zazzle a few years back and won," he continued. "Zazzle is a platform that allows you to order merchandise easily online and even had a waiver for people to sign regarding copyright. Harley-Davidson successfully proved in court that knockoff merchandise produced without a license is a violation of copyright regardless of the waiver the end-user signs.”

Intellectual legwork

If we are to accept the statement, commonly attributed to P.T. Barnum, that “There’s a sucker born every minute,” that means that the promotional products industry is susceptible to attacks from numerous sources, including, as Ross noted, people who sell goods outside of such occasions as sporting events and concerts. Their rampant roles as brand hijackers, along with the aforementioned examples and instances where clients seek to circumvent conventional business transactions, comes down to, in so many words, laziness.

Though White has never needed to tackle brand hijacking head on in his employment with BAMKO, he nonetheless realizes the breadth of the conflict that it causes and the toll it takes on brands.

“Since joining BAMKO, I can’t help but develop a much greater appreciation for the value of brands,” he said. “It’s the world we live in every day, so it seeps into how I see everything now. I think when you’re a civilian outside of the industry, you don’t intuitively understand that it is the brand itself that is valuable. For Nike, it’s not the shorts they sell—it’s the swoosh on the shorts and the way that swoosh makes you feel that drive the bulk of their value. I think folks in the branding industry inherently understand that in ways that most people, including many of our customers, may not.”

White explained that BAMKO trains every employee on the significance of clients’ brands as extremely valuable assets, and on the importance of protecting and amplifying those assets. His employer relies heavily upon its IP Protection Protocol, which compelled him to contend that the potential for infringement is something “I think our industry, in general, is far too cavalier about.

“[The protocol] is a constant, tireless process, but it’s one you have to take seriously if you’re working with the kinds of high-profile brands we work with at BAMKO,” White said of clients that include Dunkin’, Peloton, Reebok and Taco Bell. As for what has come to make brand hijacking a too-common practice in the promotional products world, he chalked it up to his assessment that most bad decisions come from the combination of laziness and ignorance.

“People are generally ignorant about intellectual property, and they are usually looking for the easiest path,” he said of the mentality that views outright rip-offs and approximations as acceptable. “When you combine those factors with fear of your clients, that’s a wicked stew that can lead to some pretty dumb decisions.”

If your eyes lit up upon seeing “fear of your clients,” know that ours did, too. Asked to elaborate, White divulged that he thinks of that trepidation as being analogous to parents who are unwilling to set boundaries for their children.

“Simply saying ‘yes’ to your kid who wants to eat Oreos and ice cream for dinner might be easier, but you’re actually not doing the kid any favors,” he explained. “Sales reps who are afraid of saying ‘no’ to clients can fall in the trap of saying ‘yes’ to anything, even if doing so is harmful to the interests of that client.”

White pointed to “a lack of sophisticated knowledge” around brand hijacking as a culprit, holding that the intangibility of concepts can cloud reasoning and lead to trademark violations. Considering the comprehension of an idea’s value component, he feels, will lead to a better grasp on the pretty-easy-to-determine difference between right and wrong.

“The good news is that some of that understanding is going to happen naturally over time,” White said. “As we increasingly lead digital lives and exist in a world where data is the most valuable asset sold by companies like Google and Facebook, people will better understand that intangible assets are among the most valuable.”

'Not the easy thing'

So, what do you do if a client asks for a design that would amount to brand hijacking? White had some simple but powerful advice: “Do the right thing, not the easy thing.”

“You’re protecting your company and looking out for the best interests of your customers [when making the right choice],” he said. “There’s no order that’s worth enough to be worth compromising that trust.”

It’s certainly easier for a large distributor like BAMKO to turn down an order than it is for a smaller distributor whose fate depends more on each individual sale. But that size disparity only makes it more important for smaller businesses to avoid brand hijacking. For a large distributor, the legal ramifications of a bad case of trademark infringement might be an annoyance. For a smaller one, they could be devastating.

“You’ve got to ask yourself what the price tag on your integrity is,” White said. “Because that’s what you’re selling.”

In admitting that he does not see the battle against brand hijacking becoming any easier, Ross added that licensed goods will likely be among the most illicit products because of the tariffs placed on them. No matter the item or request, though, distributors should do everything they can to educate themselves on intellectual property concerns so they can be prepared should a client put them in a tricky situation. Plus, the ability to guide clients on these issues is another tool in the distributor toolkit.

“Yes, I don’t see matters getting much better in terms of brand hijackers suddenly deciding to choose legitimacy, but I think that brand hijacking, or rather its effect on us, is an opportunity,” Ross said. “I think that taking a stand against it provides value to clients and dealers and leads to added credibility. The business world can be quite cutthroat. You don’t want to help the competition by inflicting wounds to yourself.”