The Price Buyers

Photo: Getty Images by Malte Mueller

Much has been written and said about why distributors need to be marketing partners for their clients, rather than order takers. But what can you do when so many customers want to buy on price? We got some answers.

Share

by Sean Norris

November 2019

Evan Mann was frustrated. Ideas Unlimited, the Memphis, Tennessee-based distributor for which Mann serves as director of strategy, engagement and innovation, had just lost a regular client. An annual project from an account Ideas Unlimited had worked with for years, gone with little warning. Mann did the right thing. He thanked the client for their business. He asked if there were any upcoming projects he could help them prepare for. “We don’t mind,” he told them. “In fact, we prefer helping our partners with the work leading up to the order process. Really, we see that as the last part of what we do. It’s in campaign development, product and brand expertise where folks tell us we provide the most value, and it’s not something we bill separately for.”

The client left anyway. And Mann had a feeling why. “They probably researched something themselves and made a decision based mostly on price,” he says. “They just sort of closed the door. And that made me feel disheartened, because I knew they saw me as a peddler, not a partner.”

Mann has seen this before, too often. And not for lack of trying. His description of Ideas Unlimited is the platonic ideal of a consultative distributor partner. He talks glowingly about “the sophistication of our work at its best,” “creating unforgettable experiences” and “the life-changing potential of meeting the right person with the right message at the right time.” That’s the kind of inspirational and forward-thinking stuff that would draw cheers during an education session at an industry event.

And yet: “I watch as our business is reduced to a transaction again and again, where client partners see us primarily as order takers and are more concerned with cost than efficacy,” says Mann. “They’re not strategic or purposeful with their use of branded merchandise, but they think they are, and it can drive a rift between you when they push back or shut down when you try to offer expertise and advice.”

You’ve probably seen this before, too. Each of the distributors (and one supplier) interviewed for this story has. Many of them deal with it regularly. It’s the reality of doing business in today’s promo-buying landscape, where online sellers, stingier marketing budgets (perhaps a holdover from the 2008 recession), new or inexperienced buyers, increased competition, low industry barriers to entry, public perception issues, and a million other factors have combined to make price a bigger issue than ever. This puts distributors in a difficult spot: either sell on price, or refuse and lose out on sales to businesses that will.

And there are plenty that will. Industry data suggests that, on average, about 40 percent of orders don’t repeat the following year. Some of those may be one-offs, sure, but the rest are buyers going elsewhere. “If you think about what that means to a distributor in the industry, it means I wake up Jan. 1 and, holy smokes, I’ve got to go replace 40 to 50 percent of my business this year just to stay even with what I did last year,” says Clay Hall, director of owner success for AIA Corporation, Appleton, Wis. “That’s daunting. It means that you’re spending an awful lot of time in this transactional space, treading water.”

That’s the most immediate downside for distributors selling on price. That kind of business might help hit short-term sales goals, but it’s not sustainable. As soon as those buyers find a lower price elsewhere, they’re gone, and you’re left spending time (and money) prospecting just to recoup that business.

But there’s a bigger issue here, too, on an industry-wide scale. As promo businesses play the transactional game and cave on price, it conditions buyers to look at nothing but price—or at least prioritize it above all other factors. That devalues the product, turning promotional items into a commodity (with potentially harmful consequences, as we covered extensively in our January 2019 cover story). And it reduces distributors to little more than order takers, which carries significant long-term business risk. Buyers can get low prices anywhere. The lowest ones likely won’t be from you. Your margins can only get so low before you can't keep up.

“We’re heading towards a future where anyone selling on price just won’t be able to compete with the industry giants like Amazon and Staples,” says Mann. “One could argue we’re already there.”

By now, this is all pretty well-documented. We know the potential endgame, for both individual businesses and the industry overall. We know the underlying causes. And we know it’s something distributors of all sizes face with varying degrees of regularity. We won’t spend too much more time talking about those things. Instead, we’re interested in what distributors can do about it. You’ve read and heard time and again about the dangers of selling on price and the need to position your business as a consultative partner for clients. This story aims to provide real insight on how to do that. Like Mann said, the future is already here. But it’s not too late to do something about it.

“Overall, I think price shopping is inevitable, and it will continue to grow,” says Gavin Long, vice president of Tugboat Inc., a distributor based in Napa, Calif. “It’s our job as distributors to sell the story and experience, not the products. Have we created monsters? Maybe. The onslaught of 24-hour (and even same-day) service has trained distributors to say yes to just about every order, and trained our clients that procrastination is OK. When you’ve got clients that are asking you to text them quotes, you just shake your head and laugh. I think we just have to embrace and adapt to the new norm.”

Here’s how. Or, at least, a place to start.

Value Is Everything

Joel Schaffer is CEO and founder of Soundline, Rockaway, N.J., a supplier of audio products. He’s been in promo for 48 years, some of them on the distributor side, and he now serves as an industry educator and advocate along with his role at Soundline. When I email him about this story, he responds almost immediately. It turns out he’s pretty passionate about the subject.

The first thing he sends me is a chart, seen below, titled “Why Me: 15 Reasons to Buy From You – The Foundation of Your Value Added.” It has 15 blocks aligned in rows, each block containing one of the many services a distributor partner provides. One block reads “creative consulting,” another “supplier identification and selection.” There’s “inventory control” and “guided delivery” and “production supervision.” The top row includes “program development” and “program management.”

It’s a simple graphic, but it’s a powerful visual representation of the distributor’s job functions, many of which buyers shopping around for T-shirts or pens aren’t likely to know about. That’s why Schaffer says it’s critical to lay it all out for potential customers—and to do so early in the relationship. “You hire an agency, you stay loyal to an agency,” he says. “An agency is a company that you have retained to do business for you. And the agent is the person who does that business for you. When you hire a promotional agency or affiliate with a promotional agency, you’re hiring them for their value added, their creative services, and everything that is in those 15 blocks.”

Here’s how this might play out in practice. Say a potential customer calls looking for large quantities of low-price product. Tell the customer you can do that for them, Schaffer says, maybe even at a better price. Then, bring the chart into play. “And just let them know that if that’s what they’re trying to do, commodity sourcing, ‘We offer commodity sourcing,’” explains Schaffer. “‘And we source all over the world. However, that’s also part of the advantage of going with us, because I can source in all four corners of the globe. And I don’t just source anybody. When you use us as your creative suppliers and consultants, we bring you only five-star companies, and those five-star companies know product safety. They know consumer liability. And what they do, and what we do ultimately for you—I’m like an insurance company. I don’t just get you a product. There’s a lot of security knowing I can get you product that’s environmentally friendly, product that’s compliant with all safety laws and so on. You’ve got a decision to make. Do you want us to do all this kind of work for you quietly and successfully? Or do you want me to have my sourcing people just get you something based upon price?’”

Right there, in that pitch, you’ve checked multiple boxes from the chart, hitting on the various value-added services you provide that might apply to the customer. You’ve given the customer information about things they may not even have considered before, but will now undoubtedly inform their purchasing decision. They may still just want a bunch of product, and at that point it’s up to you to decide if the order is worth pursuing. But now (and for the future) the customer knows the value in working with a distributor partner and not simply placing an order.

“You don’t get that when you’re buying a commodity online,” says Schaffer. “And I can give you a million case histories. If you sat in front of 100 distributors and said, ‘Raise your hand if you’ve ever gone to pick up something at the airport for your clients,’ probably 99 out of 100 will raise their hand. Customers don’t realize it, and they will forget it if it happened four or five years ago. And the referral buyer, the one who has never bought from you, but you got a referral for, wouldn’t know that these are the things that you do that bring value to the table.”

This is a point of emphasis for Mann, too. He believes the majority of clients and prospects conflate price with value—that low price equals high value. In the absence of value, price becomes the primary consideration. This happens often with companies that treat marketing as an expense, rather than an investment, he says, and especially with promotional products, which many buyers still view as an afterthought—something to throw in a trade show bag. “Products for product-sake, not necessarily tied to an advertising goal, strategy or broader purpose,” he says.

For promo distributors, then, value is everything. There’s no shortcut to winning over price buyers and differentiating your business from the often-cheaper competition. But, ultimately, success comes down to what value you bring to your clients—and, even more, how well you communicate that value to them. That’s your foundation, as Schaffer laid out. It’s the No. 1 priority. Every distributor interviewed for this story said as much.

Joel Schaffer’s 15 building blocks to added value.

Set Expectations

One of those distributors is Stacy Garrett, senior account executive for Ideation Creative Brand Management, Portland, Ore. A 20-year industry veteran, Garrett started at a large national distributor and owned her own distributorship for 10 years before selling it to spend more time working with clients. (“Best decision ever, for me,” she says.) She loves the industry and loves her job, but she knows the price struggle well. “I definitely think about this daily,” she says. “Honestly, sometimes I wish I could just ‘take an order’ instead of asking questions and making sure I am offering suggestions, because in the short term that would be so much easier and faster. But that is not how I believe I will grow my business in the long term.”

Like Schaffer, Garrett emphasizes value, especially in the early stages of the client relationship. (“What is your secret sauce?” she says. “How do you want your clients to feel when they work with you? When you make your client always look like a rock star, it is risky for them to look anywhere else.”) And one way to show your value from the jump is to be honest while setting expectations. She knows she’s not the right fit for every buyer, and she’s OK with it. More than that, she’s upfront about it with potential clients. That has two big benefits for distributors. One, it saves time putting together quotes only to have the client go with a cheaper alternative anyway. And two, it builds trust with the client from the start, as Garrett illustrated by way of example. A new customer, a referral, came to her frustrated about price creep he was seeing from his current distributor, who had started low to gain his business before gradually increasing the price. The customer also complained of slow shipping, poor printing quality and bad customer service.

“I explained to him that he could have his order fast and high quality, but it wouldn’t be the cheapest,” said Garrett. “Or he could have it be the cheapest and he would have to sacrifice in other areas. I told him that I would give him the prices up front and he would know that while the prices may increase each year, that it would not be because I came in low to earn his business. I also explained that the previous service was probably bad because the distributor wasn’t making much money on his account, and as a businessperson, he has to understand it is hard to service companies you aren’t making money from. In the end, the customer ended up working with me, and there is no question they appreciate the service level I offer and have never once complained about price.”

“I can honestly say that I absolutely want my customers to grow and flourish,” she adds. “I believe in what they do and offer, and I am thankful to be a part of their companies. That sincerity also helps them know that you will be honest with them and not take advantage of them. We are all in business after all—there needs to be profits or no one really succeeds in the long run.”

Mann believes in a similar approach. “In early conversations I set an expectation for what we can do and what we can’t do, and differentiate us by saying something like, ‘Anyone can sell you a pen with your name on it, and in the age of Amazon, a lot of them can do it quicker and cheaper than me. But at Ideas Unlimited our No. 1 value is integrity—we stand behind everything we sell, we will learn and vigorously adhere to the standards of your brand, and we will never compromise on quality, because we know that your brand is your most valuable asset. Having spent more than 40 years in business, we’ve built relationships with suppliers and manufacturers whose standards are as high as ours, and we rely on those relationships to get jobs done when others can’t. Beyond this, we’ve dedicated ourselves to becoming advertising experts. We know what messages move people and how to deliver them effectively. We’d love to partner with you in your marketing efforts.’”

Focus on Quality

A pitch like this or Schaffer’s, or a conversation like Garrett’s, is a good starting point. Each succinctly outlines your value proposition and sends a clear message that your business is about far more than products and price. But don’t ignore the product side. Most customers who seek out a promotional products distributor are looking to buy promotional products, after all. And the initial way you pitch or talk about product offering can go a long way toward securing the initial sale, while simultaneously putting the focus on quality over price.

That’s a big part of the strategy for Dan Lunoe, regional vice president for Pittsburgh-based distributor HDS Marketing’s Cleveland office, and his team. Most buyers want quality items, Lunoe says, especially if they’re putting their company’s logo on them. A promotional product is an extension of their brand. A good quality item can elevate a brand. A low quality item, one that breaks or gets thrown away, can hurt it. Promotional products professionals know this, but customers may not—at least not right away. And it can be a powerful concept for buyers when it clicks. That’s why Lunoe recommends reinforcing it from the outset.

“After explaining that to my clients and showing them the actual difference in products, they usually see the benefit of going with a higher-quality item,” he says. “An item/category that I think really brings home this point is drinkware. When I started, drinkware was all about cheap, cheap, cheap. Now we sell more higher-end double-wall insulated drinkware items that are $10 and up, and lots of YETI items that are $45 and up. People want their brand associated with quality and sometimes other name-brand items. There are always times when price will win over quality for specific events, etc. By quoting with a good-better-best approach, you can show your client that lower-price options are available, but usually they’ll go with the better or best, and are happy that they are associating their brand with quality products versus the cheapest option out there.”

Really Know Your Customer

Rod Brown founded MadeToOrder Inc., a distributor based in Pleasanton, Calif., in April 2003, and most recently served as its chief financial officer before stepping down from daily operating roles earlier this year. He helped grow MadeToOrder revenue from $5 million in 2003 to more than $24 million in 2018, and he’s a founding member of Reciprocity Road, an eight-distributor buying group with a combined $200 million in 2018 revenue that’s focused on “vision, good design, smart marketing, philanthropy and power partnerships.” This subject—helping distributors avoid the order-taker trap—is a big deal to him, so much that it’s part of the reason he took on a reduced role at MadeToOrder. He wants to be an educator, a speaker at industry events, a contributor to stories like this one. And he has a lot to contribute.

Brown, too, believes it’s all about showing what value you bring to your customers. But before you can do that, he says, you have to really understand them. In this magazine, we talk about this all the time—knowing your customer’s goals, industry, budget, audience. For Brown, that’s the bare minimum.

“I never felt that I was the consummate sales guy,” Brown tells me. “So I had it earn the right to be in there and in discussion with a customer. For me, that meant that I had to do some homework, right? I’d look at a company and I would understand, at a minimum, what’s their revenue, what’s their head count, what’s their go-to-market strategy—that is, are they going to market through their own captive sales force? If so, how many of them are there, 10 or 1,000? Do they go through value-added resellers (VARS)? Do they go through stocking distributors? Do they do one thing in North America and another thing internationally? Understand how they go to market and the general size and scope of the business.”

Brown says he’d read up on the press section of a customer’s website to see what company news they were excited about. If it was a publicly held company, he’d look them up in the SEC database for any additional information that might be of value. He’d even go as far as to buy a small amount of stock in any customer’s business that was publicly traded, as it not only gave him access to any information the company provided shareholders, but also showed just how invested he was in that company’s success. It’s an almost obsessive level of detail, to be sure. But it shows the customer, right from the start, how far you’re willing to go to meet their needs.

“If I couldn’t prove my value, then fine,” says Brown. “But I wanted to feel confident that I earned the right to be there and hopefully have them feel the same about me, that I’m different than the other guy who’s just, ‘What’s your best price on a coffee mug?’ That just didn’t seem to me to be the essence of what I wanted to sell. I wanted to sell that we were engaged and involved and informed, and we’re trying find intersections of what they do in their marketing efforts with what we do in the promotional products space.”

“If I felt that way, then hopefully I would exude that and I would build trust,” he adds. “I have this slogan that says, ‘You’ve got to grab both the heart and the wallet from a customer.’ You can’t get just one. One of them doesn’t do you any good. They might love you, but they never spend any money. Or they spend some money with you, but they don’t love you. Then that’s the end of the relationship. You’ve got to get both.”

This step is so important that many larger distributors have entire departments dedicated to it. AIA Corporation, for example, has its Owner Success team, designed to provide AIA’s network of some 300 distributors with business development resources, including coaching, data and market information they might not otherwise have access to. Clay Hall, who’s been with AIA for four years and recently took over as director of owner success, says the team was essentially formed in response to today’s increasingly transactional promotional products market. And one of its top priorities is researching customers to help distributors maximize their value.

“Our team spends a lot of time on helping the distributor understand and know their customer, and not just what business they’re in,” says Hall. “Are they another construction company or are they a software company? It’s what are they doing, who are their competitors, who are their customers and how do they go to market? How do they socialize the company internally? What’s the vibe, the culture? And what do they say externally? Read their blogs. Read their social media posts. Really get to know the customer from that perspective. And then you can bring value and come with informed decisions about what products you might recommend or what programs you might recommend, versus calling to follow up on the quote on the tumblers.”

For Hall, knowing your customer also means knowing their communication preferences, from channel—phone call, email, text message, Facebook message, etc.—down to the frequency and cadence. (“Just ask them,” he says. “‘How do you prefer I communicate?’ saves a lot of time and headache.”) And it means knowing who to talk to and, crucially, developing more than one contact at their company.

“You’re kind of one phone call from disaster if you only have one or two contacts,” says Hall. “And as customers become more complex and the industries continues to evolve, it takes more people to make that decision on who to do business with than it ever has. We shared some statistics with our community back in July at our national sales meeting that suggest that, on average today, about seven people are involved in a complex sale. So if you know just one, you’re not getting the deal. And in fact, you may not even know the deal is an opportunity, because they make a decision and tell you after the fact.”

A display in Tugboat Inc.’s showroom at its Napa, Calif. office.

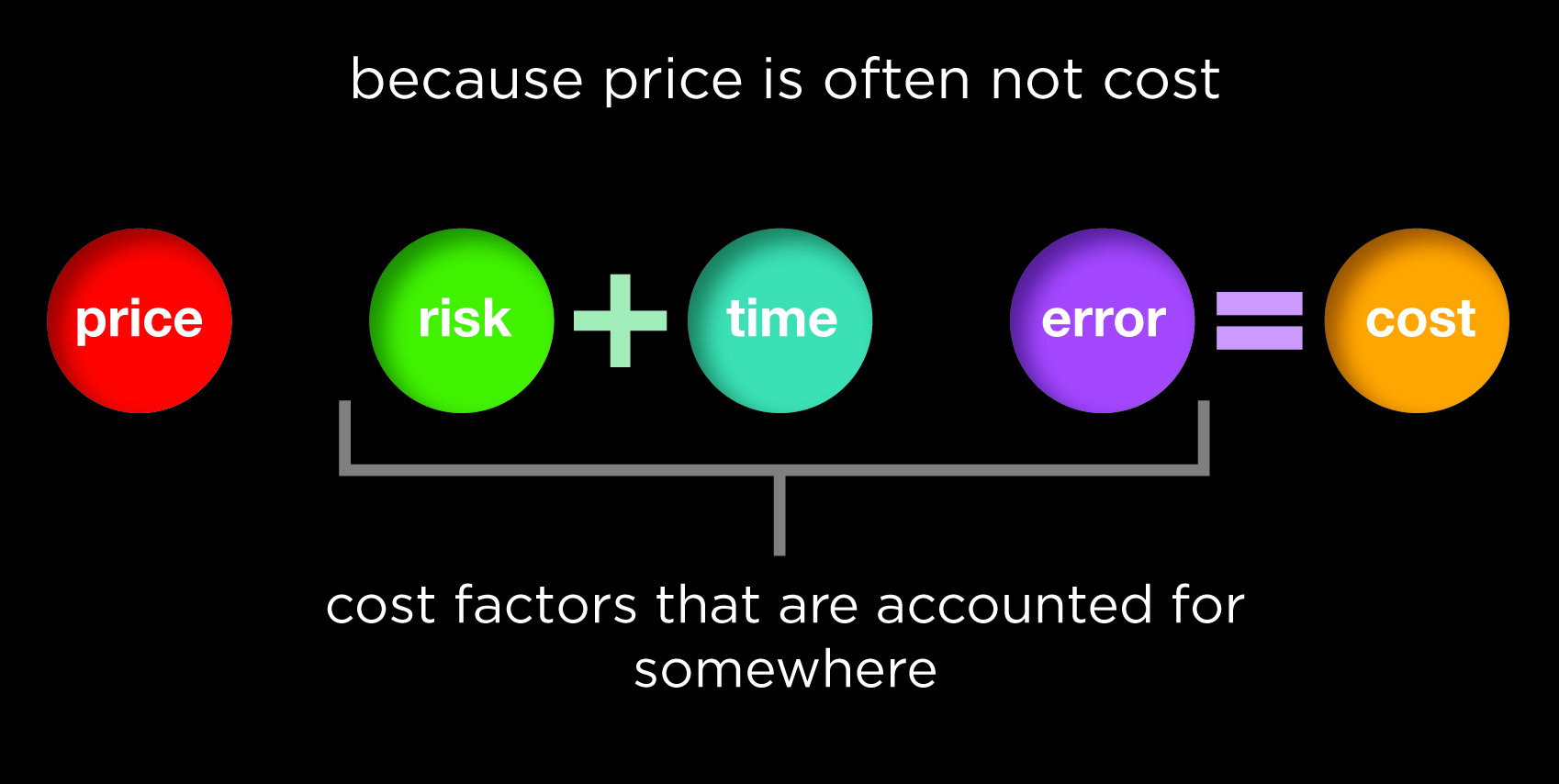

Reduce Friction

Brown has a chart, too. (See below.) It’s similar to Schaffer’s, in that it communicates the distributor’s overall value proposition, but it does so in a different and perhaps more striking way. It’s a simple equation—price [plus risk, plus time, plus error] equals cost. “Because price is often not cost,” it reads. It’s brilliant in its simplicity, in that it illustrates why it might cost a little more to work with a good distributor partner, while also showing where those extra costs come from. It effectively rolls all of Schaffer’s building blocks into the bracketed section, condensing them into three buckets (risk, time and error) and eliminating them from view.

It’s a fitting metaphor for the distributor’s role, because once you’ve communicated your value and earned a client’s business, you don’t necessarily want the customer to think about those things anymore, at least not actively. When a customer buys promotional products online, it takes only a few clicks to order. The “Amazon Effect,” as it’s sometimes known. The goal of the distributor should be to come as close as possible to replicating that customer-facing buying experience while doing all the value-added things—sourcing, graphics, shipping coordination—behind the scenes, with minimum input from the client. Low friction. Just like Amazon, but with a real person handling the details, addressing customer needs and providing a level of service no website can match.

“Think about all the touches that are involved in an order,” says Brown. “If a customer says to me, ‘Look, Rod, I’ll get you the purchase order—it might even be after you deliver, but I’ve got to have this stuff on Friday,’ no problem. I’ll send them a confirmation email: ‘Here’s all the details of the order. Here’s what I’m doing for you. I’m going to assume that everything is good to go unless you say stop or no. All you have to do is respond stop or no. But if we’re good to go, you don’t have to do anything. Here’s the information. Here’s what’s going to happen. Here’s how I’m going to deliver it. Here’s every piece of information one time. You don’t have to do anything more.’”

Brown gave the example of a T-shirt order. If the customer has to call and ask if their shirts are shipping today, that’s high friction, he says. Reduce that friction by preemptively reaching out to the customer to confirm that their items are shipping. Send them the tracking number, or if it’s not available yet, tell them you’ll send it when it is. When you send the tracking link, you can even tell them the stage of shipment their order is in so they don’t have to click. That’s just one area you can save customers time and touches. There are plenty of others. The artwork proofing process, for example.

“If I’ve done my job right, when the order is confirmed to my customer, I’ve given them, ‘Here’s your layout, here’s what it’s going to look like,’” says Brown. “I don’t burden my vendor with creating that proof. We’ve already done it when we entered the work. We’re delivering, ‘Here’s the item, here’s the artwork on the item, to size, in the right position, meets all the production specs. It’s not oversized or undersized. Here it is. Here’s the whole thing.’ Because if we demand that the vendor sends us a proof of the order, we push that to our customer, we demand that the customer get back to us with an approval, then we route that approval back to the vendor, that’s a lot of touches in there. If it’s wrong, we’ll replace it for free. But we’re not going to be wrong. We’re going to do this right and deliver a robust dataset to the customer right now, and save all those touches.”

Another strategy Brown recommends for making things easier on customers? Don’t just sell a product—sell distribution. Once buyers receive their shipment of 10,000 pens or 5,000 mugs or 1,000 T-shirts, it’s typically up to them to figure out what to do with all those items, how and where they’ll deploy them. Brown says many companies can get hung up at this stage, stockpiling products without an effective plan to get them into end-users’ hands. Smart distributors can get involved in this part of the process at the outset of the sale—with potentially significant rewards. Brown explained how.

Imagine a customer wants to promote a new product to its network of 1,100 value-added resellers, he says. You pitch them pens, decorated with a logo and tagline and packed in bags of 50 with a printed instruction set for each VAR: Here are 50 pens to write up your next big order. We’re coming out with a new product we’re really excited about. Please put these pens to work in your offices and then with your customers, and know that this new product is breaking November 1. “I’ll do a 1,100 of these packs, with this instruction set built into the pack,” Brown says, acting out the pitch. “I’ll give them to you in a mailable envelope—1,100 envelopes already done, ready to go to each of your VARs. If you want to give me a VAR, I can sign an NDA with you that I won’t share that information, and we’ll direct drop-ship these from the factory straight to them. Or, I’ll ship them all to you, you keep your data, and you reship them out to your VARs.”

“That is so different than coming in and saying, ‘I want to sell you 55,000 pens,’” he says. “But that’s what that pitch just was—55,000 pens. You’ve got to sell distribution. Sell the idea of how the customer can get rid of it all. Because the more you can sell distribution, the more likely you are to sell more product, get more business.”

Rod Brown’s chart illustrating the difference between price and cost.

It's OK to Take an Order (and to Walk Away)

Evan Mann remains optimistic. For all his frustration with the clients he’s seen walk away, he knows Ideas Unlimited has the right, well, ideas. He knows that not every client wants a collaborative partnership, that some will leave or buy elsewhere no matter what you do. And, like Stacy Garrett, he knows not every client is a fit for his business. He also knows that, sometimes, it’s OK to take an order, as long as it makes sense from a time-versus-profit standpoint and doesn’t keep you from developing relationships with more valuable clients and prospects. Gavin Long feels the same way, if cautiously so.

“I think there is some potential opportunity with the price shoppers, but the stakes are higher,” he says. “It’s a 100 percent volume play that is tough to maintain, because remember—someone will always be cheaper. You’re going to be working just as hard as the rep or company that works on healthy margins, but you’ll be making less. If an order goes bad (for whatever reason), you’ve got less wiggle room to work with. Cash flow will be tighter. So if you’re stuck with mostly price-shopping clients, I would challenge you to go find one new client where you can maintain a healthy or normal margin and see how it changes things. And in theory, for every new non-price driven client you find, you can cut two or three of your price shoppers loose.”

Still, it’s not impossible to convert some of those price shoppers into higher-value accounts. Mann says that if a customer calls and already knows what they want, Ideas Unlimited will process the order. Then, once the customer receives the order, they’ll check in to make sure the customer is happy, and ask to schedule a short follow-up call to discuss potential future projects and learn more about them. If the client won’t make time, Mann says, it’s a good indicator that they’re only interested in placing orders. But if they do agree to a conversation, it opens the door for future business. On that follow-up meeting or call, Mann will ask questions about the customer’s business and bigger-picture advertising and marketing goals. He’ll gather information he might need to brainstorm solutions and discuss next steps, usually offering to develop a proposal on how Ideas Unlimited can help the customer achieve specific goals. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t. But it’s almost always worth a try.

“I like to say that Ideas Unlimited has three types of clients: clients to grow, sow and let go,” says Mann. “If a customer sees us as a consulting partner and has the potential to deepen their business with us, that’s a relationship we want to grow. We have a number of partners who’ve been with us for decades and we’ve grown together—those are ideal clients. There are others on our radar, maybe in our sales funnel, with strong marketing budgets that demonstrate a degree of marketing savvy and have the potential to become long-term partners—these are the clients we work to sow, to begin working relationships with and to turn into long-term partners. The customers we seek to let go are mostly transactional, driven primarily by price, and they require an inordinate amount of time and attention. They’re those customers that take up hours on the phone or make you go back and forth on an order that barely breaks even. If we can’t transition them to a less time-intensive solution (a company store, our website, etc.), we let them know that we’re just not a good fit and try to recommend another resource for them.”

Dan Lunoe agreed that every client, price-buyer or not, presents an opportunity for future business, even if it’s not always directly. Most of the time, it’s easy for distributors to keep those lines of communication open. And it could pay off long term. “I would keep reaching out to them with low-cost touch-points like email blasts or direct mail,” he says. “Your persistence might eventually pay off—maybe not at that company, but maybe they have a friend, family member or former co-worker that they will pass your name onto. I think persistence is key. Keep your name in front of them, and I believe eventually you will have an opportunity to earn their business or someone’s they know. I love it when someone thanks me for a self-promo piece and tells me it was the greatest thing they have received, and they showed it to someone they know and they might be calling me. That one mailer that I sent to my client might help two to three of their friends, family or co-workers know who we are, and maybe contact us for new business opportunities—which is the goal, to have people calling us because they want to work with us.”

Ultimately, it’s up to you whether you take orders from price buyers, turn them away or try to convert them. (Or a little of everything.) Do what makes the most sense for your business. Hopefully, if you struggled with it before, the strategies and advice in this story help you out. Whatever you do, just be careful out there—and never compromise on your value.

“Don’t give them a reason to shop around,” says Long. “Show them your value. Give them some additional suggestions or a cool case study as to why you’re pitching this particular product or idea. What about packaging or kitting? Be human and add some personality or subtle humor to your emails. Don’t be afraid to pick up the phone and talk to them. Thank them for their order and ultimately do what you say you’re going to do. Once you prove to your client that you’re worth the extra money, you won’t have the price discussion again.”

“You do no favor to your customer by underpricing your deliverables, because you then cannot invest in the robust services and future and vibrancy that your customer really is going to need over the years ahead as a lifetime partner,” says Brown. “Underselling leaves your own company and your own business anemic, and you will not be able to deliver the value equation that your customer needs. If you cannot sell that to your customer, then that customer is shopping dollar stores. You’re not Wal-Mart. You’re Nordstrom. Walk away.”