Photo: Getty Images by Miguel Navarro

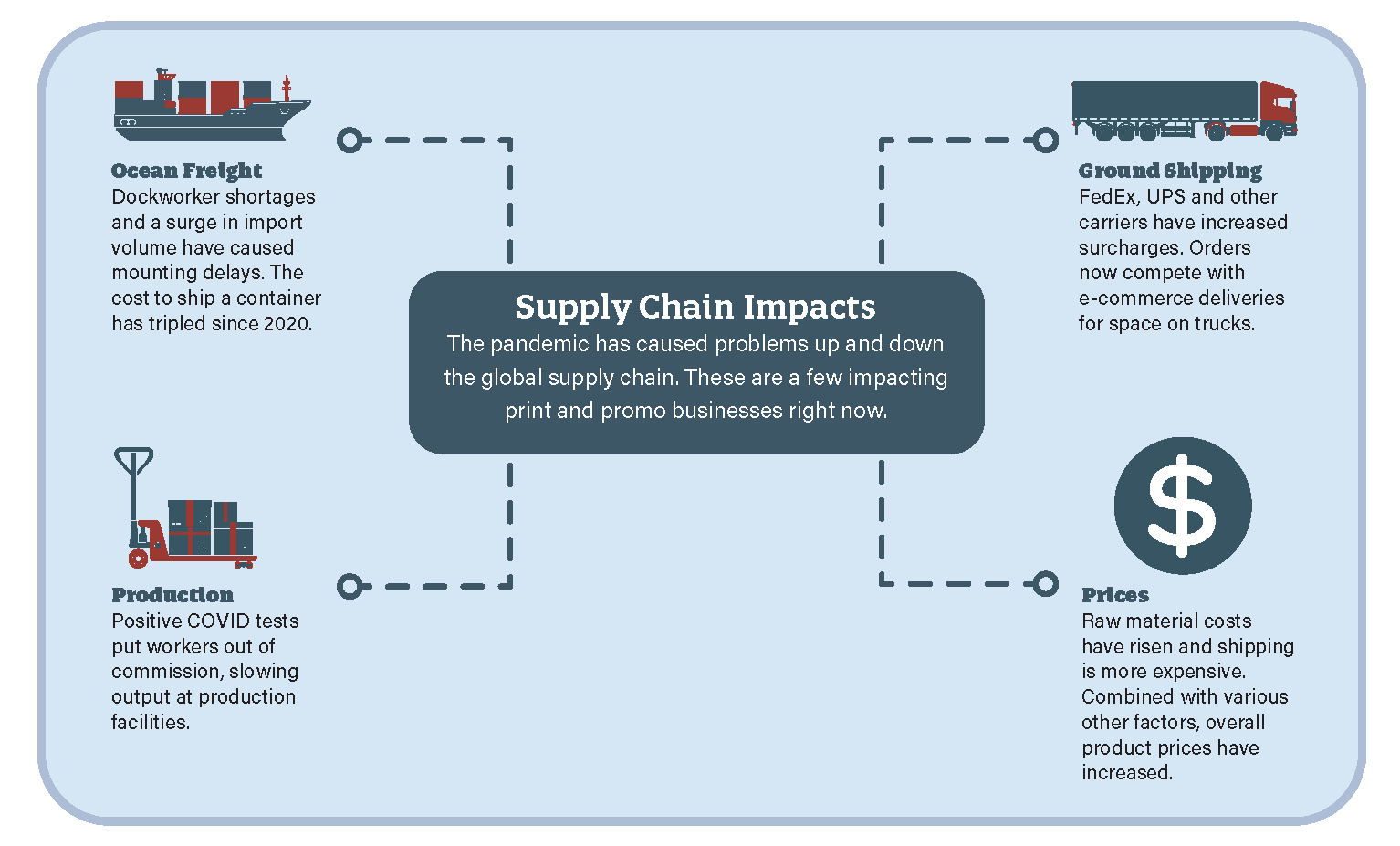

Shipping delays, production issues, price increases—the pandemic is wreaking havoc on the global supply chain, with real consequences for print and promo businesses. Which impacts are temporary, which are long-term and what actions can industry companies take?

Share Article

by Sean Norris

February 2021

The Port of Los Angeles sits in San Pedro Bay, an inlet on the Southern California coast that opens south into the Pacific Ocean. Its location, on the eastward side of a squarish chunk of land that juts down and out from the coast like a rogue molar, affords it tremendous protection from the Pacific’s waves and wind. Its deep water, mostly natural but augmented by dredging operations over the years, allows it to handle even the world’s largest container ships. The port has 113 miles of on-dock rail (with a significant expansion project underway) and prime access to major rail freight networks that disperse cargo across the U.S. Most importantly, the port has an optimal geographic location—on the West Coast, a short (by maritime standards) 15-day sail from the vast manufacturing empire of China across the Pacific.

These factors have combined to make the Port of Los Angeles the busiest port in the U.S. Its neighbor across the bay, the Port of Long Beach, is third busiest, owing to the same factors. Together, the ports form the San Pedro Bay Port Complex, which is either the fifth- or ninth-busiest port in the world, depending on the metric. The complex handles 40% of total U.S. container imports each year and more containers per ship than any port complex in the world. An infographic from FreightWaves, a shipping and logistics news site, helpfully notes that the twin ports handle the metric-ton equivalent of 440.9 billion basketballs each year. The same infographic calls the San Pedro Bay Port Complex “America’s Gateway to the World.” In 2018, the complex handled a total of 17.5 million TEUs (twenty-foot equivalent units, the standard unit of measure for shipping containers)—about 48,000 containers per day.

So it was alarming that, on Tuesday, Jan. 19, the port complex was at a virtual standstill. More than 40 ships sat at anchor in the waters outside the ports’ 25 cargo terminals, waiting for a chance to unload. Some had been there for weeks. It was the most severe bottleneck the ports had seen since a labor dispute six years ago. This time, it was the product of an unrelenting surge in shipping volume as American retailers restocked inventories depleted earlier in the pandemic and American consumers turned to e-commerce in record numbers. That, and there simply weren’t enough people to unload the ships. The Los Angeles Times reported the following day that more than 700 dockworkers at the San Pedro Bay Port Complex had tested positive for COVID-19, with hundreds more on virus-related leave. Eugene Seroka, executive director for the Port of Los Angeles, estimated that 1,800 workers were not on the job—12% of the ports’ total dockworkers. Executives at the International Longshore and Warehouse Union called the infection rates “catastrophic.”

“Without immediate action, terminals at the largest port complex in America may face the very real danger of terminal shutdowns,” California Reps. Nanette Diaz Barragan and Alan Lowenthal, whose districts include the ports, wrote in a letter to state health officials a few days before. “This would be disastrous not only for the communities of the South Bay, but also the entire nation, which relies upon the vital flow of goods through these ports."

Port officials say they don’t expect shutdowns. But, even so, the situation neatly encapsulates the chaos that has unfolded—and is still unfolding—throughout the global supply chain. The San Pedro Bay Port Complex is a model of efficiency, as well equipped as any facility in the world to handle complex and evolving shipping and logistics challenges. Yet the pandemic has pushed the port to its breaking point. The supply chain is (to use the technical terminology) a mess, with real consequences for the print and promo industries. Some of those impacts will be temporary. Others will be permanent or longer-lasting. All will require industry suppliers and distributors to rethink the way they do business and reevaluate their roles in the supply chain, now and in the future. Here’s how.

Container ships and tankers anchored outside the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach on Feb. 1. The ports were in the midst of the worst backlog they’d ever seen due to shipping volume increases and worker shortages brought on by the pandemic. Photo: Getty Images by Mario Tama

China

The print and promo industry has dealt with supply chain disruption before, most recently in the ongoing aftermath of the Trump Administration’s aggressive tariffs on China and, before that, in the global fallout from the 2008 recession. Compared to the pandemic, of course, those barely qualify as disruptions—the difference between an unskippable ad before your YouTube video and your laptop catching fire as you press play. “[This] was an unprecedented event, in that the disruption came from both the supply and demand side,” said Joshua White, senior vice president of strategic partnerships for BAMKO, the top 20 distributor based in Los Angeles. “The industry simply had not anticipated having to fight a two-front battle and wasn’t prepared to respond adequately. The nature and type of customer demands dramatically shifted overnight at the very same time as trade, shipping and supply disruptions made the supply-side of getting products that much more difficult.”

On the print side, much of the disruption has been production-related. Positive COVID tests have sidelined workers, slowing output at production facilities or forcing them to temporarily close for sanitization. On the promo side, it’s been that and more. Early on, in the mad scramble for PPE, demand far outstripped supply, and overseas factories that had never produced PPE before lacked experience or failed to meet standards. Restrictions on commercial air travel reduced shipping capacity by as much as 50%. Existing U.S. trade tensions with China, coupled with ever-changing Chinese government regulations for shipping PPE, made exporting even more difficult. Regulations forced some suppliers, like BamBams, based in Manassas, Va., to stock large amounts of PPE rather than drop-shipping it from China. That created its own set of problems. “As supply caught up to demand and the costs plummeted, we had to take some losses on the inventory,” said Dan Taylor, president and owner of BamBams. “It also created warehouse space challenges.”

Many of these difficulties have one thing in common: China. The vast majority of promotional products are made there, and the issues suppliers and distributors faced sourcing PPE in the first few months of the pandemic raised renewed questions about the long-term viability of the industry’s China-dependent supply chain. Even as the early PPE madness subsided and factory relationships returned to something resembling normal, mounting shipping delays, like those at the San Pedro Bay Port Complex, have made China’s outsize role in the promo supply chain harder to ignore. Never before have the risks involved in relying so heavily on one manufacturing partner-country been so apparent.

That last sentence, of course, could have been written at just about any point in the last 20 years. Tariffs, the recession, post-9/11—any time there’s been a global shakeup, the prospect of finally moving on from China, or even simply relying slightly less upon it, comes back up. Every time, the answer is the same. China is almost impossible to move on from. It has the mature supply chain, raw materials and technical expertise that no other country can match. Industry suppliers have deep, well-established partnerships with Chinese factories and long-standing relationships with the people who run them. Dan Jellinek, executive vice president for The Magnet Group, Washington, Mo., counts many of those people as friends, and credits those close relationships for helping his company—and the industry—navigate the pandemic. “I know my relationships with my suppliers in China through this past year, the craziest year that anybody has ever seen, were what got us through,” Jellinek said.

More than anything, though, manufacturing in China remains inexpensive. The Magnet Group makes some products in the U.S. and sources others, like bags, in Vietnam, Pakistan and India. Plenty of other promo suppliers are doing the same, with some even manufacturing mostly or entirely in the U.S. But certain products, like double-wall stainless mugs or electronics—huge categories in promo—simply can’t be made outside of China at a price point U.S. consumers want to buy while leaving viable margins for suppliers and distributors. The pandemic isn’t going to change that. As Jellinek says: “China is China.”

Still, even if there are no sweeping changes, there will be minor ones. While BAMKO has extensive sourcing relationships in China (it has offices in Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Ningbo), the company been diversifying its supply chain for years. That shift figures to continue, and will likely accelerate. White expects USA-made products to receive a permanent boost in demand, and he acknowledged that certain categories are relatively easy to migrate outside of China. Some of them—apparel, for example—are already on the move.

“There’s a lot more country diversity on the apparel side than in, say, electronics or some of the drinkware that our customers are looking for day in and day out,” said Jellinek. “South America is an option, Vietnam is an option. There are a lot more options on that side. Plus you also have the cut-and-sew element. That’s where you also see product going outside China, even if the product itself—the raw materials—are still coming from China. Our towel line, Towels by Magnet, all comes out of South America, which has been great for us as China has rolled into the Chinese New Year. We all need to diversify our supply chain.”

Those changes won’t be immediate. It’ll be some time before distributors feel their impacts, if they do at all. The same can’t be said about prices. Raw materials costs are increasing. Demand has been volatile. Labor shortages caused by the virus have given way to higher overall production costs. This is not limited to China—manufacturing costs have risen everywhere during the pandemic. But add in existing tariffs, rising shipping rates (more on that in a minute) and a fluctuating exchange rate for the U.S. dollar versus the Chinese yuan, and Chinese goods are now more expensive than they were just a few years ago. Suppliers can only absorb those added costs for so long.

Short term, that means higher prices that distributors will either need to absorb or pass on to their customers, similar to what the industry has already seen with tariffs. Long term, Jellinek expects prices to fluctuate, necessitating greater communication and transparency from suppliers. China will still be cheaper than the alternatives, but actual prices may be hard to predict. “Going forward, I think you’ll see price changes more reoccurring,” he said. “No different than the supermarket. It won’t be at that frequency, but prices will change. They’re going to have to change with more fluidity over the next little while.”

"COVID has been a hard lesson in many ways, one of which being a call to action for businesses to be significantly more proactive in determining needs further in advance."

—Thomas D’Agostino Jr., CEO, Smart Source LLC

Shipping & Delivery

As the mayhem at the San Pedro Bay Port Complex makes clear, shipping is where the print and promo industries will feel the pandemic’s most immediate supply chain impacts: delays, longer lead times, increased costs. This is already happening. According to the Freightos Baltic Index, the average cost to ship a container has risen by 80% since November and tripled since the start of 2020. Inland haulage charges, incurred when moving a container to a freight station once it arrives at a port, have doubled. A few weeks ago, the Port of Los Angeles had a huge surplus of containers from the nonstop deluge of cargo arriving each day. That led to container shortages in China, delaying shipments even before they got to America’s already-clogged ports. Suppliers have had to decide between paying more to mark containers priority or taking their chances with delays.

The situation is highly volatile, which is part of the problem. (Example: In the rush to send back containers to ease shortages in China, the Port of Los Angeles ended up with its own shortage.) No one knows what to expect next or when things will normalize, and it’s likely to stay that way for some time. About all anyone can do is adjust lead-time expectations and prepare for price increases. “We are advised to add an additional 14 days minimum into ocean supply chain forecasts,” said Taylor. “Distributors need to be aware when planning for their larger import orders this year. It will likely be the end of 2021 for things to return to normal.”

It’s not just the ports, either. Taylor said air cargo rates were double or triple the express rates in 2020, and while he expects those to return to normal sooner than ocean rates, there are ground shipping challenges, too. FedEx, UPS and DHL have all increased fees in 2021 (a FedEx PDF listing surcharge changes is five pages long). And, of course, there are delays. “Promo and PPE shipments had to compete with space for commercial goods, whose import volumes increased during 2021 … with more people staying at home increasingly engaged with Amazon and other e-commerce retailers,” said Taylor. “FedEx and UPS have had significant difficulty managing the demand for space with increased e-commerce shipments. Further, they are providing logistics services for the vaccine, which added to the congestion.”

Slower ground shipping means more orders may need to ship by small package air, which, you guessed it, means higher costs. It also means more orders will need to be drop-shipped, as suppliers and distributors look to eliminate extra shipping where possible to reduce the risk of delays. This might work in distributors’ favor—drop-shipping has already taken off during the pandemic, with distributors able to position it as a value-added service for their customers—but only if the orders actually make it on time. Either way, drop-shipping should remain a fixture as industry companies rethink and reconsider their overall logistics capabilities after the pandemic ends.

“Warehousing, distribution and technology will be paramount in the post-pandemic world,” said White. “It’s tough to put the genie back in the bottle—a decentralized workforce is likely to continue long after the vaccine, which will mean more drop shipments and the need for robust distribution infrastructure. Distributors with competitive shipping rates, close carrier relationships, robust warehousing/fulfillment services and regional plants will be ahead of the curve.”

Action

White expects many of the pandemic’s negative supply chain impacts to be temporary. International freight costs will eventually come back down, he said. Raw materials in limited supply will again become widely available. Domestic shipping will return to reliable, predictable form. Supplier inventory levels will stabilize. In-person events will resume, gradually shifting demand from PPE back to traditional print and promotional products. It might be tempting for distributors to sit around and wait for those things to happen. After all, pre-pandemic, with the promo industry humming along to the tune of $24 billion a year, distributors could get away with a more passive role in the supply chain, reacting to upstream changes without doing much to influence their outcome—or simply not paying much attention to supply chain issues at all. But White believes that’s no longer an option for distributors.

“They’ve got three choices: lead, follow or get out of the way,” he said. “At BAMKO, we’ve committed to the path of leadership by diversifying our supply chain, making massive capital investments in technological and distribution infrastructure, diversifying our client base, and broadening the scope of services we have to offer. Those commitments have positioned us to grow massively in a time of great disruption and set us up for more growth as the uncertainty created by the pandemic continues to unfold in the coming years. The status quo that has allowed distributors to remain complacent and still grow over the past decade is gone. It’s not coming back. Distributors can accept that reality and restructure their organizations so that they are capable of navigating a rapidly changing landscape, or they can fade into oblivion. Closing your eyes and wishing for things to go back to how they were in 2019 is not a sound or defensible strategy.”

There are actions distributors of all sizes can take to shore up their supply chains and better position themselves against future disruptions large and small. They can diversify their clientele to rely less on a single customer or industry. They can diversify their supply base to rely less on a single supplier or geographic region. They can work toward vertical integration that reduces the need for third-party services, granting more control over processes and costs. They can invest in technology and distribution, two areas White says are more critical than ever. “Events and corporate functions have already started to give way to less-centralized programs shipping across the country and globe (new hire kits, digital events, incentive programs, etc., shipping at least in part to people’s homes),” he said. “This requires organization, distribution capabilities and, often, nimble digital platforms.”

Those are big changes and significant investments that will take time to implement. For smaller distributors lacking financial resources or larger ones not agile enough to adapt quickly, some of them may not be possible, at least not on a short enough turnaround to have noticeable near-term impact. But there are things distributors of any size can do right now. Taylor suggested communicating earlier and more often with suppliers and customers, setting clearer expectations for orders, planning for longer production and delivery times, and encouraging customers to plan ahead and place orders as early as possible. Even just having these conversations is a good start—a step toward reframing the distributor’s role in the supply chain from a reactive one to a proactive one.

“As both manufacturers and distributors, now is the time to take stock of what we have learned from doing business in the COVID environment, certainly while these lessons are fresh,” said Thomas D’Agostino Jr., CEO of Smart Source LLC, the distributor based in Suwanee, Ga. “We see some positive impacts coming away from the pandemic. COVID has been a hard lesson in many ways, one of which being a call to action for businesses to be significantly more proactive in determining needs further in advance. This pertains to our customers as well as our own operations as we work with our suppliers. … [From] a strategic planning standpoint, the pandemic has made all of us realize that the unimaginable is actually possible. Therefore, contingency planning has become a much more active part of our strategic agenda.”

The most impactful thing distributors can do right now is something the best ones already do: work continuously to strengthen industry relationships. As Jellinek said earlier, it was his long-standing partnerships with suppliers in China that got him and The Magnet Group through the early part of the pandemic. Taylor said BamBams’ established factory partners in China and Turkey were instrumental in the company’s overnight transition to PPE. BAMKO’s extensive sourcing relationships helped it grow in 2020 even as the rest of the industry contracted by 20%. Other distributors had similar success, for similar reasons. We don’t know what supply chain challenges the pandemic still has in store or how long the current disruptions will last. That makes it all the more necessary for suppliers and distributors to have partners they can depend on.

“All those things in the supply chain that were so important to me with my suppliers, we need to be closer to that between distributors here and suppliers here,” said Jellinek. “Now’s the time to hunker down with your preferred people and work together as true partners to get through this together. It takes all of us. Relationships and being loyal have been a savior in the supply chain for me and for The Magnet Group during an unbelievably challenging 2020. The reward for that is not running away. The reward is continuing the relationship and appreciating the relationship—and hopefully more to come.”