Purdue Pharma and Promotional Products: Marketing America's Opioid Crisis

Purdue Pharma's headquarters in Stamford, Conn. Source: Flickr by Raymond Clarke

This is the story of a company using marketing to push on Americans a product that could kill them. This is a story of greed, and loss, and delayed corporate responses, and regulatory failure. This is the story of a promotional campaign, and everything that came after.

This is the story of how Purdue Pharma marketed America's opioid crisis, the surprising role promotional products played, and where we go from here.

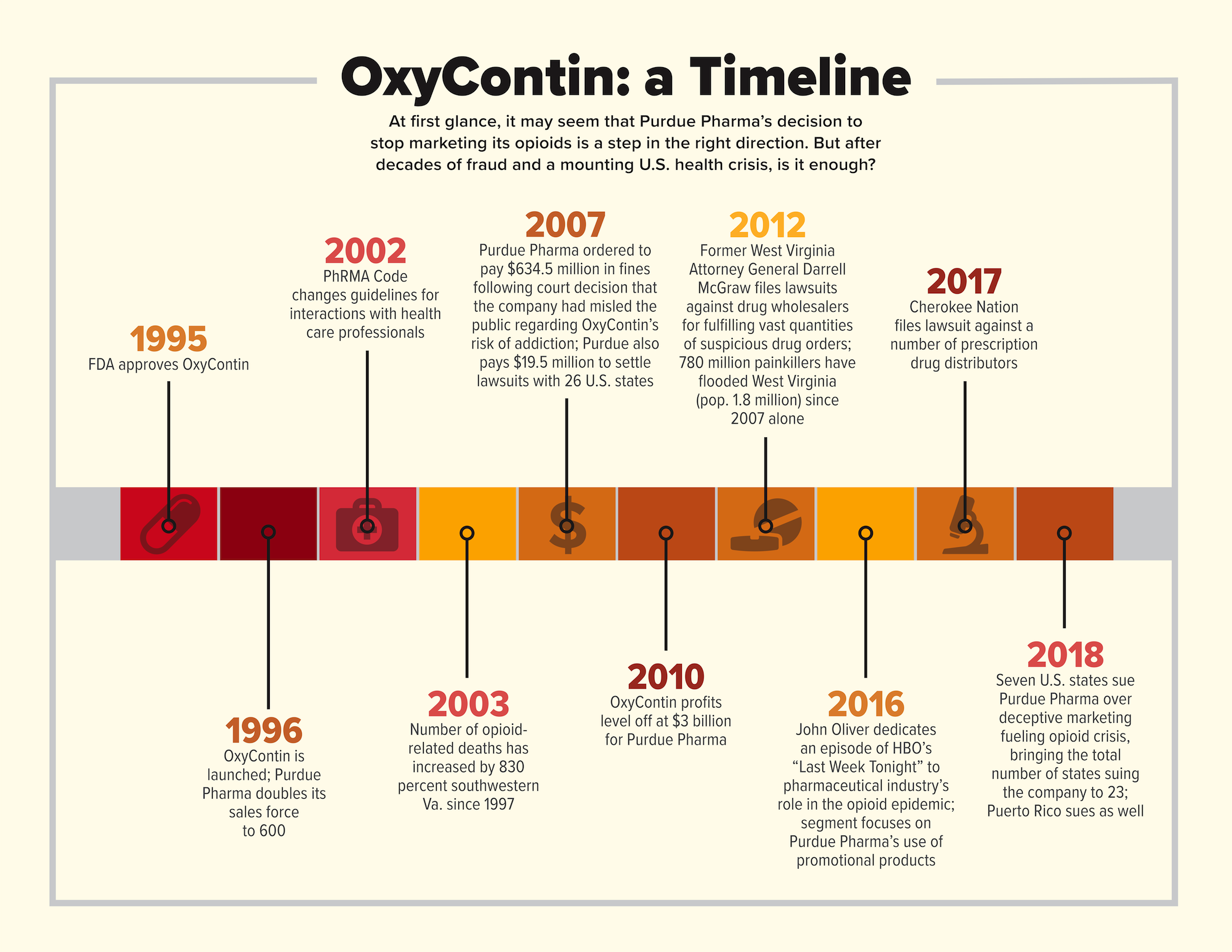

Purdue Pharma’s promotion of OxyContin over the years has been notable in its ability to convince doctors to prescribe extremely high doses of the painkiller on the strength of a marketing strategy that depended to a significant degree on promotional products such as clocks, fishing hats and pens. The use of these items has been largely curtailed over the years, especially after 2002’s PhRMA Code on Interactions With Health Care Professionals made it clear that pharmaceutical representatives were no longer to provide gifts unrelated to health care, such as golf balls and sports bags. Despite this, the legacy of Purdue Pharma’s use of seemingly innocuous products to promote the highly addictive OxyContin lives on.

Although the pharmaceutical giant cast its decision to cease promotion of opioid products as a restorative maneuver, it is clear that other factors contributed to the move. Under threat of numerous lawsuits, and faced with the declining profitability of OxyContin for a variety of reasons, including the rise of generic drugs, Purdue has ultimately made a business decision—not an altruistic one. This behavior should not seem out of character to anyone familiar with the multi-billion dollar company’s practices over the years, especially with the methods it used to promote OxyContin. In fact, Purdue has misled the public for years with regard to OxyContin’s effectiveness and addictive properties, and it is clear the company used promotional products, among other marketing strategies, in order to do so.

It began in the late 1980s, when Purdue Pharma, owned by the Sackler family, realized it was about to lose its main source of revenue. The company’s most popular and lucrative drug, a morphine pill called MS Contin, was coming up on the end of its patent. Executives at Purdue foresaw a huge loss of revenue as generic versions would begin to flood the market and drive down the price of MS Contin. And so, the company decided that it would combine a time-release technique already used for MS Contin—designed to make the morphine last 8-12 hours—with a cheap, common narcotic known as oxycodone.

This plan, conceived in response to an impending business crisis, led to the creation of OxyContin, the most popular and lucrative prescription opioid of all time. How did an otherwise cheap narcotic like oxycodone reach such heights? As it turns out, it doesn’t have much to do with the drug’s reliability, but rather with the largest and most persistent marketing campaign ever conducted for a prescription narcotic, a marketing campaign that, in hindsight, contributed to the death of thousands of Americans who had the misfortune to be prescribed OxyContin.

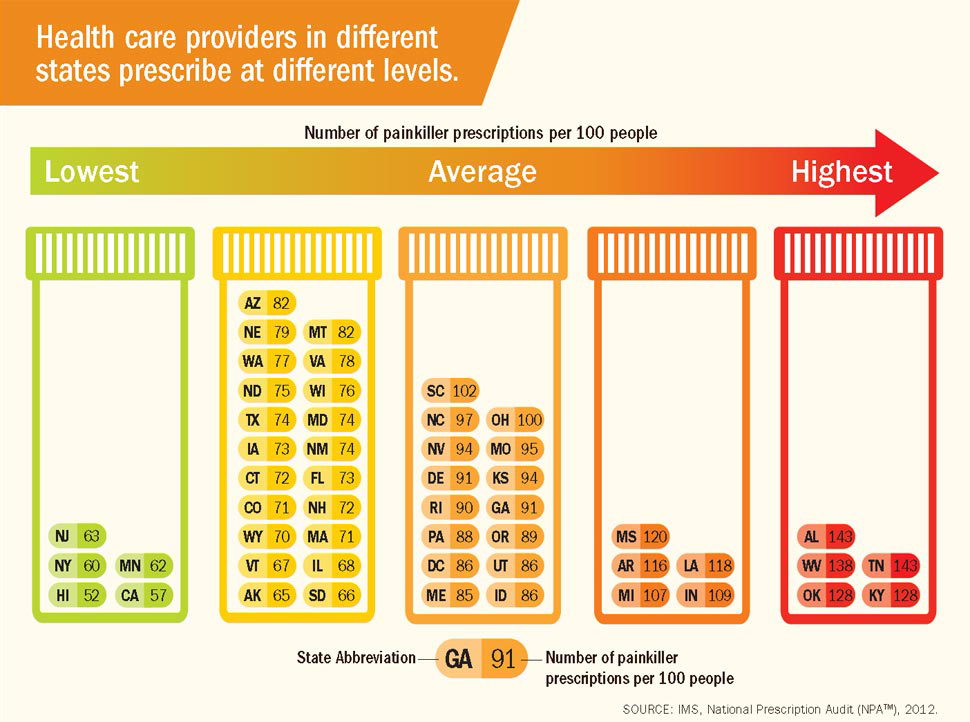

Although narcotics have been used in the past for pain relief, opioids in particular were only used before the 1990s to treat pain brought on by terminal illnesses and injuries, specifically late-stage cancer. This changed in the late ’90s, and the rise of OxyContin had everything to do with it. According to Art Van Zee’s 2009 report in the American Journal of Public Health, Purdue’s promotion of OxyContin for treating pain unrelated to cancer led to a tenfold increase in OxyContin prescriptions for chronic pain. This increase constituted a change from 670,000 prescriptions in 1997 to around 6.2 million by 2002. During that same time period, prescriptions for cancer-related pain saw a fourfold increase.

The popularity of OxyContin as a treatment for chronic pain was unprecedented before the late ’90s. In fact, OxyContin was so popular that its sales quickly surpassed those of MS Contin, the very drug it had replaced. In fact, only three years after its release, sales of OxyContin more than doubled those of MS Contin at its peak, the Los Angeles Times reported. By its fifth year in existence, OxyContin generated more than $1 billion for Purdue, a number that would increase until it leveled off at $3 billion in 2010. Purdue had a winner on its hands. The reason? Marketing.

According to the Los Angeles Times, the launch of OxyContin in 1996 saw the company double its sales force to 600. These reps were trained to pitch the opioid to family doctors and general practitioners as a treatment for conditions such as knee pain and backaches. The strength of the sales pitch? OxyContin was marketed with a twice-daily dosage recommendation, unprecedented for opioid pain relievers at the time. In order to promote this significant breakthrough, reps gave to prescribers a wide range of promotional products, including clocks and fishing hats embossed with “Q12h” to represent the dosage frequency, in order to encourage their business. Purdue even went so far as to hold dinner seminars for doctors, as well as to fly them out to resort hotels for weekend conferences about OxyContin.

Some of the promotional products Purdue Pharma and other pharmaceutical companies used to market and promote prescription drugs to doctors prior to 2002's PhRMA code revisions. Source: STAT

Overall, the company spent $207 million on the launch of OxyContin, to get the message out that a new opioid could be prescribed for a wider range of maladies than ever before, and at a twice-daily dosage frequency. This kind of marketing was not unusual for pharmaceutical companies. The problem, however, was that OxyContin never actually worked as a twice-daily drug—and Purdue knew it.

In fact, in the same period that saw OxyContin’s prescriptions increase tenfold for Purdue, the company spent six to 12 times more on promoting the drug than it had spent for MS Contin. The same goes for Janssen Pharmaceutical Products LP’s marketing expenditure for Duragesic, an OxyContin competitor. But why did Purdue go to such exaggerated lengths to promote a superior product? Couldn’t OxyContin’s treatment capabilities have spoken for themselves? The questions are important, but their answers aren’t exactly mysterious. The simple explanation is that OxyContin wasn’t actually as effective as it was supposed to be, and Purdue knew it.

When Purdue released OxyContin in 1996, it did so under the FDA’s approval of its use as a 12-hour drug. However, according to the Los Angeles Times, in early trials designed to study the efficacy of the drug, patients routinely dropped out or took supplemental painkillers—known as “rescue medication”—well before the 12-hour dosage was supposed to lose effect. To compensate, researchers simply changed the rules of their trials to allow for patients to take supplemental painkillers if need be. In doing so, Purdue got its FDA approval, and OxyContin hit the market as a Q12h opioid painkiller. Purdue saw its profits soar. Once doctors and patients realized that the effects of the drug often wore out before 12 hours was up, some prescribers began writing prescriptions for an eight-hour dosage frequency. That’s when Purdue realized it had a huge problem on its hands.

In order to protect its business, Purdue reps were told to convince physicians that there was no need to put patients on eight-hour dosing regimens, since 100 percent of patients that took part in Purdue’s studies had pain relief on the 12-hour regimen. This, of course, was far from the truth. According to Vox, Purdue stood by its claims for years, even telling doctors that the problem was not the dosage frequency, but rather that the doses were too low.

There are a few problems here, the first being the issue of dosage frequency. When patients found the effects wearing off before their next dose was due, many began to take OxyContin more frequently than prescribed, leading to a cycle of dependency that could easily lead to addiction and even overdose. For patients who’d had their doses increased, this meant that they were given large quantities at a time with little to no supervision as to how or if they took them as prescribed, assuming that the pills didn’t end up in the wrong hands to begin with. This had devastating results.

In Boone County, W. Va., for example, which had a population of 22,816 as of 2016, Larry’s Drive-In Pharmacy filled countless suspicious prescriptions, dispensing 10 million doses in 11 years. According to the Charleston Gazette-Mail, West Virginia had rules in place that required drug companies to report suspicious drug orders. In 2012, when former Attorney General Darrell McGraw filed lawsuits against drug wholesalers for fulfilling vast quantities of suspicious drug orders, the pharmacy board put in place to regulate those orders began to receive a flood of reports that would eventually surpass 7,200 in number. Before that, although the regulations and pharmacy board had been in place since 2001, there had been only two such reports.

According to another article from the Charleston Gazette-Mail, drug firms flooded West Virginia—a state with a population of around 1.8 million—with 780 million painkillers from 2007 to 2012. At a local level, the numbers are even more dramatic. Kermit, W. Va., a town with a population of 392 people, received 9 million hydrocodone pills over a two-year period. Such ridiculous numbers are tragically common throughout the nation. In a lawsuit filed by the Cherokee Nation against prescription drug distributors like the McKesson Corporation, Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen, CVS, Walgreens and Walmart, the true scale of the epidemic comes into focus. In the 14 counties that make up the Cherokee Nation, 845 million milligrams of opioids were distributed. With an average pill size of 20 milligrams, this adds up to 360 pills per prescription opioid user in the Cherokee Nation.

For users of OxyContin in particular, this surplus of pills created a deadly combination when mixed with the unaddressed issue of proper dosage rates. As users realized that a Q12h regimen was insufficient, shorter dosage frequencies turned into higher dosages, which turned into increased demand and led to the exponential growth of opioid addictions and overdoses around the country. This cycle of dependency very quickly became a death spiral. In southwestern Virginia alone, the number of deaths related to opioid prescriptions rose from 23 in 1997 to 215 in 2003, an increase of 830 percent. Purdue’s decision to spend unprecedented amounts of money on marketing, combined with its decision to cover up OxyContin’s inefficacy, created a perfect storm in which the opioid crisis was allowed to grow and persist.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The code, which Purdue adopted, also addressed the use of branded promotional items, stating that products such as golf balls and sports bags were no longer allowed to be distributed because they did not benefit patients or support medical or scientific research or education. This meant that no more hats, clocks, plush toys or music compact discs (that’s right, there was a promotional CD called “Get in the Swing With OxyContin”) could be given to physicians by Purdue sales representatives. This was across the board for the entire pharmaceutical industry.

For anyone in the promo industry back then, if the 2002 PhRMA guidelines aren’t familiar, then the effect they had on the industry certainly should be. The guidelines were so strict that they hurt many industry firms, and practically decimated what had become one of the most lucrative verticals for promotional products at the time. Since then, business in the pharmaceutical sector has never been the same for the promo industry.

We asked Cliff Quicksell Jr., director of marketing for iPROMOTEu, Wayland, Mass., about how promotional products companies usually initiate business with pharmaceutical companies after the change.

“It depends on the relationship,” he said. “… I would venture to say that more times than not that connection could go through an ad agency that has a relationship with a distributor and the distributor acts as a third-party provider—it works in various ways.”

Quicksell told us today’s pharmaceutical marketers typically look for items that keep their brands top-of-mind with doctors and other medical staff—pens, notepads, mugs, stethoscope covers and the like. That’s a major change from pre-2002, when pharmaceutical companies could directly promote specific drugs and buddy up to medical personnel with incentive items to encourage prescriptions. Now, it’s about education.

If you feel that you are promoting something that harms others, then you should choose not to engage with that opportunity.

“With the PhRMA ruling, it is critical for distributors to develop programs utilizing print and promo, along with packaging, to aid pharma companies in educating the public and health professionals on their brand(s),” Quicksell said.

After establishing some basics of the business, we got to talking about Purdue Pharma and its announcement that it would cease marketing and promotion of its opioid products, including OxyContin. In light of the opioid epidemic, and knowing that Purdue misused promotional products and advertising to misinform the public with regard to the addictiveness of OxyContin, we asked Quicksell for his thoughts on whether or not there is anything the promotional products industry can change in order to avoid similar situations in the future. While he wasn’t then aware of Purdue’s actions, Quicksell did provide some insightful commentary on the ethics involved with conducting business in the promo industry.

“I am not aware of how Purdue allegedly misused promotional products to market their drugs,” he admitted. “People regularly do things that are not so smart. I believe it is a conscience issue—if you feel that you are promoting something that harms others, then you should choose not to engage with that opportunity."

With everything that has been revealed in the years since 2002, however, including the 2007 court decision that proved Purdue had misled the public about OxyContin’s risk of addiction and forced the company to pay $634.5 million in fines, it’s a good time to evaluate the promo industry’s role in marketing the drug. The purpose is not to assign blame, but rather to ask if there are any precautions that could be taken in order to ensure that nothing like it ever occurs again.

One might argue that this isn’t the responsibility of the promotional industry, that these marketing campaigns are the responsibility of the brands they represent alone. This may be true in a business or legal liability sense, but it’s important to note that scandals of this magnitude can impact the image of the promo industry overall, as well.

For instance, in 2016, when John Oliver dedicated an entire segment of his weekly HBO series “Last Week Tonight” to the pharmaceutical industry’s role in the opioid epidemic, he called out several examples of promotional products used in the marketing strategy for OxyContin (see around 7:22 of the below video). The promo industry, which typically stays out of the spotlight in order to play a crucial supporting role for more visible brands, was suddenly being played for laughs in front of millions of television viewers.

A minute-long clip on a premium channel late-night show might seem like a minor thing. But for an industry already working tirelessly to prove (rightfully) that it's more than just cheap swag, it's a bad look. And that's only one trouble area. Product recalls, no matter how minimal, have the potential to generate cautionary or critical headlines and stir debate over regulation and compliance. Those stories are always attractive to the media, but the headlines are the least of the promo industry's worries.

While the industry has been mostly lucky so far, every recall for a defective or dangerous product has the potential to wreak havoc on a brand's reputation—and for promo businesses, that means clients' brands, too. Imagine a hypothetical scenario where a branded power bank is recalled for catching fire and injuring multiple users. The recall notice might hurt the supplier and distributor of the product, but it's the brand represented on the item that's likely to take the brunt of the blame with consumers.

"Sometimes, the financial and reputation impacts of a product recall are insurmountable," writes Trevir Nath for Investopedia. "Many small companies have declared bankruptcy as a result of defective merchandise. Larger corporations with more flexibility must work quickly to maintain customer loyalty and, most importantly, shareholder confidence."

Luckily, there are industry initiatives dedicated to ensuring that product safety standards are followed. Quality Certification Alliance was formed in 2008, and PPAI’s Product Safety Awareness Program is a requirement for all industry companies that want to access the PPAI marketplace via sponsorship, trade show, advertising or exhibit space. Initiated in response to government product safety regulations, PPAI's program encourages industry companies to adhere to rigorous safety standards in hopes of avoiding the controversy and regulatory backlash that can ensue following a recall.

And recalls aren’t the only thing the industry has to worry about. Recently, there has been scrutiny over the use of promotional products in political campaigns. Though there has been a long tradition of business between governments and the promo industry, some regulatory entities have begun to question whether or not a promotional product constitutes a gift, which could lead to a violation of ethics codes in some states. In Denver, the City Council’s Board of Ethics recently debated this very subject, questioning officials as to the value of promotional products they’d received. Apparently, the five-member panel has set in place a guideline that requires officials to turn down gifts worth more than $25, as anything exceeding that value would be likely to influence policy decisions. Needless to say, this could have a major impact on how city offices and departments use promotional products.

Elsewhere, Canadian politics and policy watchdog iPolitics has scrutinized promotional products spending by Canada's government, and Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin signed an executive order capping the state's "swag" spending at $10 million a year—a whopping $18.5 million reduction from current levels. That move, designed to ease Oklahoma's budget crisis, has clearly painted promotional products as a wasteful expense. It doesn't take an MBA to realize how that move could impact the industry if other states or organizations take notice and follow suit with their own 64 percent cuts to promotional products budgets.

Purdue Pharma's history of marketing OxyContin.

Take the NRA as an example. After the recent mass shooting at Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., brands that had associations with the gun-rights organization saw their reputations take a hit online. In response, many of those brands, including Hertz, Enterprise, Metlife and First National Bank, announced they would be ending their partnerships—which included discount programs for members—with the NRA.

While this type of public outrage is usually reserved for brands that are nationally recognized, the promotional products industry is not immune, no matter how much it tries to stay out of the spotlight. If the John Oliver episode on pharmaceutical marketing is any indication, it’s clear that promotional products used to market controversial or ethically questionable brands and campaigns could find their way into the public spotlight once again. If the promo industry wants to avoid this kind of negative attention, as well as the type of damage it took after the PhRMA guidelines changed in 2002, it will have to be more judicious when deciding what brands it will promote.

As for Purdue Pharma’s decision to stop marketing its opioids, there’s really only one way to look at it. The move smacks of irony in the same way that Purdue’s supposed commitment to combatting the opioid epidemic does. This is Purdue’s mess, and it only took years of coverups, deflections and obfuscation until lawsuits and the specter of declining profitability finally encouraged Purdue to end its opioid marketing. The scariest thing, however, is that the scope extends far beyond Purdue.

As of this writing, seven more U.S. states have filed new lawsuits against Purdue Pharma for its role in the opioid epidemic, directly citing the company’s use of deceptive and fraudulent marketing to support its prescription painkillers. In addition, 16 other U.S. states and Puerto Rico have filed their own lawsuits for the same reason, as well as at least 433 separate cities and counties whose cases, naming big-name defendants such as Purdue, J&J, Teva, Endo, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health and McKesson, have been consolidated in a federal court in Cleveland, Ohio.

As for the promotional products industry, this can only be seen as an opportunity to learn and to grow. While it may be no secret to industry professionals that promotional marketing is an extremely effective tool for brands, others may be surprised to learn that merchandise could have played such an important role in marketing OxyContin and other opioids to the public. With this in mind, it's up to each individual promo industry business to be careful what brands it promotes, and how it promotes them.

“If I sell someone a car and they use it in the commission of a crime, what do you think the automobile industry could do to ensure a car was never used again for such an act?” said Quicksell. “Some time ago, not PhRMA-related, this guy put $10,000 on my desk, and wanted 2,000 T-shirts printed with the promise of thousands of more. Some would have thought the shirt funny, others despicable—yet no one would have been the wiser. But I would not print the shirts. Hopefully you understand how these relate.”