The

Big

One?

Photo: Getty Images by AdrianHancu

Amazon launched Merch Collab, its latest on-demand merchandise service, in 2018. What is it? And what does it tell us about Amazon’s future plans for promotional products?

Share Article

by Sean Norris

January 2020

The blimp hovers low over a lake, a blob of white against the mountain ridge in the near background, and drifts ominously from right to left across the frame. A few seconds into the video, something shiny drops from a hatch in the blimp’s underside, and the camera quick-zooms as nine more somethings emerge—drones, fanning out in multiple directions. The video cuts to the blimp and its drones flying in formation over a small-city skyline, then to the drones flying back to their mothership. It ends abruptly at 39 seconds, freeze-framed on the logo on the blimp’s side: Amazon.

The video was fake, the blimp CGI. But, the internet being the internet, it went viral anyway. The original video, posted to Twitter on March 31, racked up 651,000 views, with assorted GIFs and reposts (at least one scored to “Ride of the Valkyries,” of course) nabbing many thousands more. On social media, people freaked out. “This right here is borderline dystopian,” one Twitter user posted in April, as the video first made its way around. “Amazon is officially taking over the world,” posted another in December, 13 minutes before I wrote this paragraph, long after the video had been widely debunked.

Beyond the admittedly nice CGI job by its creator, a digital artist based in Japan, it’s easy to see why so many people bought it, and continue to do so now, months later. Amazon really does hold a patent, filed in 2014, for an “airborne fulfillment center” that would function pretty much exactly as the fictional version does in the video, right down to the blimp. (There are diagrams and everything.) The company has been trying to make drone delivery a thing for the better part of the decade, with Jeff Bezos appearing on CBS’s “60 Minutes” in 2013 to declare that the tech would be ready in “four or five years.” Outside of a few test trials, that hasn’t happened yet.

But also: It’s Amazon. It’s the closest thing we have to dystopian cyberpunk corporate villain. We’re all just a little bit afraid of it, even as we happily order $5.99 replacement iPhone charging cords with one-click two-day delivery. We’re practically, ahem, primed to believe it would do something like this. That it can do anything. That, at some point, it will upend everything the same way it upended retail, and web services, and logistics, and voice assistants, and anything else Bezos sets his sights on. It probably will.

____

That’s why, whenever Amazon does anything, the promo industry pays attention. We scrutinize its every development, waiting for The Big One—the move that finally takes Amazon from future threat lurking on the periphery to direct competitor eating our collective lunch. (The reality is somewhere in between, but we’ll get to that.) In 2018, a story on Amazon expanding its Merch by Amazon service was the eighth most-read article on our website. This year, a story on an additional, relatively minor Merch by Amazon expansion ranks in the top 25.

So it’s a little weird that Amazon Merch Collab, launched in May 2018, has largely escaped notice. When I asked a random sampling of 10 industry folks if they’d heard of it, only two said they had. (All 10 said they’d heard of Merch by Amazon.) I myself only found out about it recently, while researching another story. That’s likely due to Merch Collab’s relatively quiet rollout—it was announced at the 2018 Licensing Expo in Las Vegas to little fanfare, and has had few if any big media stories about it since. But here’s why we should be paying more attention.

First, the description, directly from the Merch Collab landing page: “Merch Collab is a new licensing program where brands collaborate with qualified designers and manufacturers to create the world’s largest selection of branded merchandise for fans. Merch Collab makes licensing as easy as ‘Buy now with one click.’ Brands simply approve and promote products. Amazon tracks sales and pays out royalties.” Second, the tagline at the top of the page: “Empowering brands and small business owners to create merchandise together.” And, third, everything we know about Amazon’s on-demand merchandise capabilities already.

If you’re waiting for The Big One, Merch Collab by itself probably isn’t it. It’s not the proverbial drone-deploying robot mega-blimp come to destroy us all. But it may be an indicator of Amazon’s larger plans for branded merchandise.

Buildup

First, some background. Merch by Amazon launched in September 2015 as a way for individuals to design and sell custom T-shirts. Creators could upload their artwork, and Amazon would do the rest, listing the shirt, printing it on-demand, and handling fulfillment and shipping. Sellers would earn a royalty on every shirt sold. Designers flocked to the platform, recognizing the potential to make some easy money through passive income (that is, a kind of set-and-forget revenue stream). It got so big so fast that Amazon switched to an invitation-only application not long after launch.

The platform also attracted major brands, including Disney, Nintendo, Budweiser and NBC. Analysis by MerchReadyDesigns, a website for print-on-demand creators, turned up at least 19 big brands with at least one Merch by Amazon listing in 2018. Some, like Marvel, had more than 1,000 listings. If you search “Star Wars T-shirt” on Amazon right now, chances are your results will be mostly Merch by Amazon designs.

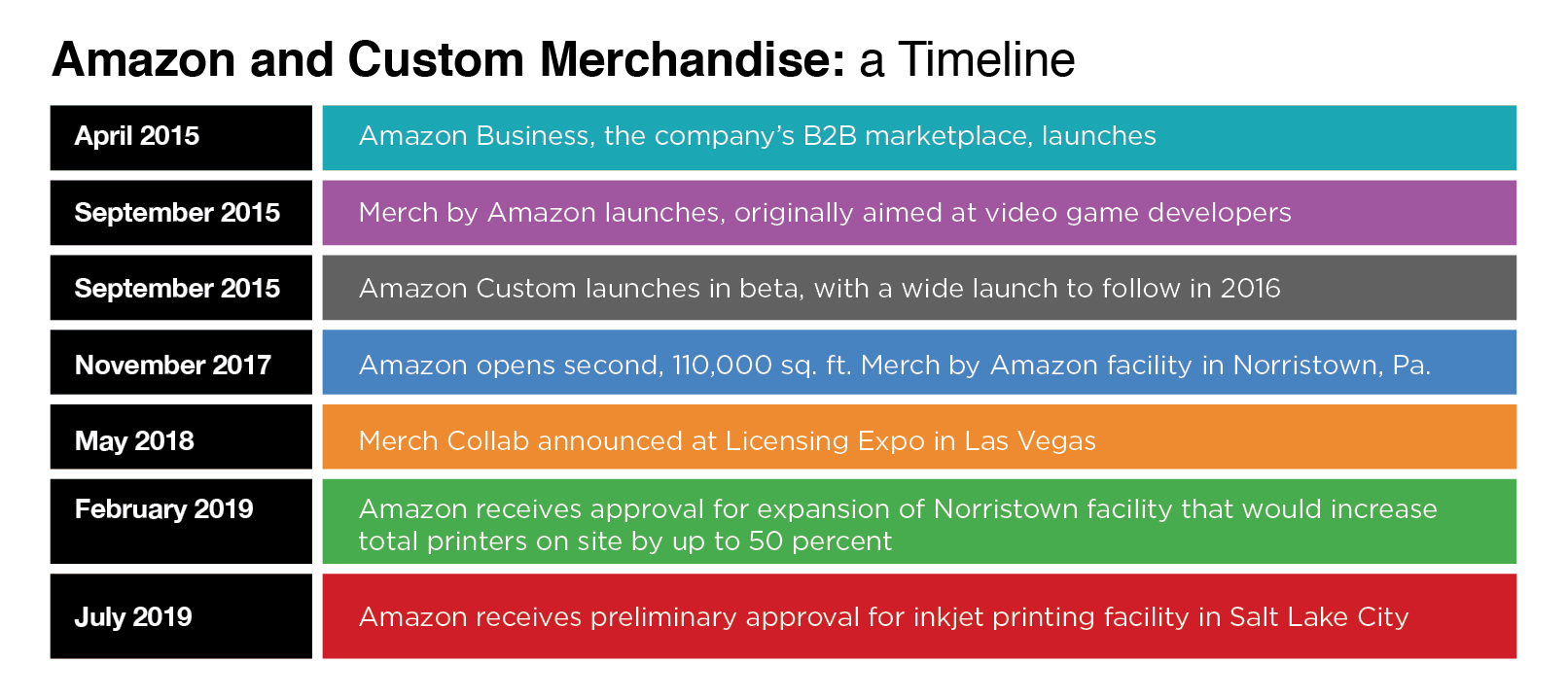

At its start, Merch by Amazon had a single printing facility, in Dallas. By November 2017, Amazon had opened another, a 110,000 sq. ft facility in Norristown, Pa., adding an additional $150 million worth of Kornit Digital on-demand textile printers and acquiring an 8 percent stake in Kornit. (In 2018, it opened another Merch by Amazon facility in Poland to service the U.K. and German markets.) In early 2019, Amazon had obtained permission from environmental regulators to expand both the U.S. facilities, with permits for the Norristown location allowing for up to 72 textile printers, up from the original limit of 48. In July 2019, Amazon received preliminary approval for an inkjet printing facility in Salt Lake City. All the while, the company expanded its Merch by Amazon product offering, adding sweatshirts, long-sleeve tees and PopSockets, and experimenting with phone cases and other items.

“I can tell you anything that you can print on demand, we’re considering it,” Miguel Roque, director of Merch by Amazon, told Yahoo Finance in 2018. “The key thing is that we are able to produce it at scale, and with a degree of quality that we think both brands and customers will really be satisfied with.”

Then there’s Amazon Custom. Launched in 2016, the platform works like Spreadshirt or Zazzle, allowing anyone to create and buy custom merchandise. Sellers can apply to list their products, though unlike Merch by Amazon, Custom requires sellers to fulfill orders themselves. Shoppers can upload their own images and customize text. There are 20 different product categories, including apparel, office, electronics, personal care and automotive.

In the Sports & Outdoors category, you can buy a railroad spike knife personalized with the names of your groomsmen, or a three-pack of ping pong balls customized with a picture of your dog. In men’s apparel, you can get a Gildan polo in 13 different colors, digitally printed with any design you want and shipped for free. (“If you have a business you need some of these!” reads one five-star review for the polo.) On the Amazon Custom FAQ for sellers, question No. 8 asks if the platform can be used to personalize products for business buyers. “Yes, our image customization feature is a great way for businesses to design a product with their logo,” the answer reads.

Merch Collab

Here’s how Merch Collab works. Brands that want to sell on the platform apply online. Once they’re approved, they set up a list of brand guidelines—logos, colors, available intellectual property, etc. Designers use those guidelines to create and submit artwork, which the brand can review and approve or reject. Approved designs go live on the brand’s dedicated Amazon storefront. Amazon handles production, fulfillment, returns, exchanges and customer service, and provides real-time analytics on what products are selling. The brand gets two-thirds of the royalties from each sale, and the designer one-third. On the sale of a $19.99 T-shirt, for example, the brand would receive $3.49, the designer $1.74, and Amazon the rest, covering the item’s costs and Amazon’s fees.

It’s essentially an extension of Merch by Amazon, but designed to attract brands rather than individual sellers. It offers the same product assortment and uses the same on-demand printing equipment and facilities. Amazon carefully vets the designers, requiring a separate Merch Collab application only available to artists already accepted to Merch by Amazon. Various users in the r/AmazonMerch sub on Reddit have indicated that Amazon approves only a small number of applicants for Merch Collab, with some users speculating that designers are required to sign nondisclosure agreements if accepted. (My attempt to reach an Amazon representative for more information on Merch Collab went unanswered.) The designer approval process apparently involves multiple stages.

Merch Collab launched with a small lineup of brands that also took part in the testing phase, including CBS Consumer Products, Cartoon Network and YouTube mega-star Shane Dawson. Since then, it appears to have added only a few more. (Neil DeGrasse Tyson, semi-disgraced astrophysicist and guy who loves to “well, actually” your favorite sci-fi movie, headlines the “Brands We Are Working With” section of the Merch Collab site.) The merchandise selection, which mirrors Merch by Amazon’s, is still fairly limited. And the platform still requires brands to sell the merchandise through Amazon, rather than purchasing bulk quantities for sale or distribution elsewhere.

But that might not remain the case. In a box near near the bottom of the Merch Collab landing page, next to “apply” buttons for brands and designers, there’s a third button: “Apply as a manufacturer.” In the program structure section just above it, Amazon notes that Merch Collab currently supports only on-demand products via Merch by Amazon, but that it is “exploring other categories.” (“If you think your business would be a good fit, please complete an application here,” reads the ensuing link.) On the royalty details tab, a table at the bottom lists third-party manufacturing royalties by category, with a note that manufacturers will be charged separate Merch Collab fees in addition to the standard Amazon seller fees. The product categories in the table, with a few small exceptions, match those available on Amazon Custom.

It does not appear that Amazon has activated this part of the Merch Collab platform—yet. But it certainly looks like the functionality is built in. And if or when Amazon enables this feature, it will allow brands, designers and manufacturers to connect within the same platform. Brands would have access to the entirety of Amazon’s on-demand merchandise printing capabilities, a small army of handpicked designers, and a huge number of third-party merchandise businesses spanning virtually every product category.

Separately, Merch Collab, Merch by Amazon and Amazon Custom aren’t all that worrisome for the promo industry. But if we view them in combination, each as a stepping stone to the next, we can sort of see the overall path taking shape. Factor in Amazon Business, the company’s booming B2B marketplace that offers everything from paper clips to bubble hockey machines and topped $10 billion in 2018 revenue, and it’s even clearer. The pieces are falling into place for Amazon to make a broader play for the B2B merchandise market. Even if this iteration of Merch Collab doesn’t catch on the way Merch by Amazon has, it might not matter.

“I see this as Amazon doing reconnaissance and data-gathering for a future project/product launch,” Bill Petrie, president of PromoCorner, told me. “If you take a hard look at Amazon’s model, they are more than willing to spend money to gather data, even if it primarily results in failure. Take Amazon Auction, a service they launched in 1999 to compete with eBay. After initial success, they couldn’t topple eBay, but the data they gathered led to the launch of Amazon Marketplace, where third-party vendors can sell used or new products alongside Amazon’s regular offerings and is now an enormous part of their revenue. They knew from the beginning that Amazon Auction would never topple eBay—and that’s the genius of Amazon: They were willing to invest in a loser to gather the data necessary to create a juggernaut. I see the same thing (potentially) happening here.”

An Amazon warehouse and distribution center located in Shelby Township, Michigan. Photo: Getty Images by RiverNorthPhotography

Threat Level

This isn’t to say the end is nigh for the traditional promotional products industry supply chain. Amazon hasn’t flipped the switch yet, and while most industry people I’ve talked to fully expect it to eventually, even that won’t bring all of promo crashing down. Large or otherwise established distributor businesses will be fine (though with the potential for margins to get squeezed further), as should any business that has invested in real relationships with customers and positioned itself as a true marketing partner. (See our October cover story on dealing with price buyers.) But there’s a subset of the industry that should absolutely be worried.

“I think the level of threat really depends on the type of distributor you are,” Phil Koosed, president of BAMKO, told me. “If you’re just acting as a middleman distributing products and not adding value in other ways to your clients, the level of threat is even higher. If you’re selling other services and have elevated relationships, the threat level is lower.” He adds: “If you’re a smaller distributor or a sales rep at a larger distributor who has no way of differentiating yourself in the marketplace, it is going to just get tougher and tougher each year. It’s a 9 or a 10 in terms of threat level for those types of folks.”

I asked each of my sources for this story to rate, on a scale of 1-10, Amazon’s threat level now and in the future. The average rating for “now” was 5.2. For the future, it was slightly higher, at 6. A few sources weren’t concerned at all, coming in at 1 or 2 for both. David Nicholson, president of Polyconcept North America (PCNA), New Kensington, Pa., was more toward the middle. He believes that, short-term, Amazon is not a major threat, as the company has yet to truly focus on promo as a strategic business opportunity. “While there is evidence of promotional products on Amazon’s site, these are primarily offered via distributors and other third-party sellers,” Nicholson tells me. “The assortment and buying experience is still very immature relative to other strategic categories that Amazon has pursued.” Longer term, he was a bit more concerned, saying it was “likely” Amazon would make some kind of move into promo, whether directly or as a reseller leveraging the existing industry supply chain.

Others, like Koosed, came in on the higher end of the threat index, even if they didn’t believe Amazon was a direct threat to their own businesses. Koosed even views it as an opportunity. “It’s Amazon—all they have to do is decide that they’re going to put a lot of people out of business, and it will happen in short order,” he says. “I fully expect that to happen in the coming years. We’re making investments to get ahead of the curve here, because we believe you can either ride the wave of technological change or be crushed beneath it. We’re going to be riding high and leveraging technology to help our sales team sell more. However, at this point it looks like most distributors are going to be caught flat-footed and asking if anyone got the license plate number of the truck that just ran them over. Accepting the reality of the massive disruption of technology has been an ongoing challenge for our industry that I hope we overcome soon. If you’re smart, bold and proactive, there’s huge opportunity here.”

In reality, there likely won’t be a single big, seismic move. Amazon appears content to go at its own pace, developing and adding capabilities over time and gradually expanding them, testing and learning. For the launches of Custom and Merch Collab, Amazon didn’t even bother to issue a press release. When it’s ready to really enter promo, it will likely do so quietly, the culmination of years, if not decades, of building.

Besides, Amazon is already very much involved in promo. Some distributors have Amazon storefronts and have been selling through the platform for years, though it’s likely not their main channel for sales. More than that, Amazon has drastically reshaped customer expectations, forcing promo distributors to adapt to the new normal—easy ordering, faster shipping, better customer service, a seamless online experience and overall reduced friction at every stage of the buying process.

“Amazon has completely shifted the way all consumers buy merchandise, and our industry is in the merchandise sales business,” says Petrie. “Too many people keep talking about ‘when Amazon enters our space,’ as if that will happen in months or even years. Amazon is in the promotional products business now, and the longer it takes companies to respond to the rising expectations of a frictionless transaction, the closer to irrelevancy they will be.”

“At BAMKO, we’re obsessed with removing friction from the sales process,” says Koosed. “We want to make it as easy, simple and painless as possible to buy from us. In the online retail space, no one is better at eliminating sales friction than Amazon. Every one of your readers can relate to the experience of coming home and having some product sitting on their doorstep that they don’t even remember having made the decision to buy. That’s what frictionless sales looks like, and it’s what any good company is moving towards.”